Becoming a Consistent Trader

This is a topic that I've wanted to do for a while now because I think it's something with which most traders struggle at some point, myself included. You start off learning how this market works, you find some trades you like, you start having some success and then things blow up and you are, at best, back where you started, at worst you obliterate your account. You start again, things go well, and it happens again. Becoming consistent is one of the tougher things in this business so I want to talk about the approach I have taken to get there. I say this as one who took several years to figure this out so if you're struggling today, please understand this is normal. What I will show is a (mostly) finished product, but it took time and lots of mistakes for me to get to this point. My hope is that this can accelerate someone else's journey.

Planning

One of the biggest hurdles I see with traders is a lack of a coherent plan. It's easy to try and chase what's working (or appears to be working) until it blows up but that's not a path to consistency. Ideally you will have this plan all laid out before you start trading, but that likely isn't reality as you will need to change it as you learn. This is because there is no one plan. There is not one way to make money in this business. I will discuss my plan methodology but that doesn't mean it's your plan. The idea here is to show you what a plan looks like so you can make your own, whether it's based on mine or not. Everyone is different: different tolerances, styles, emotions, time commitments, etc. Use this to compare what you have and see where you may need to do more work.

A Thesis

A good plan should have a thesis. That is, foundational ideas upon which the trading plan is based. Ideally this would come first but it's quite possible that you may develop your thesis as you develop your plan. The real world isn't ideal. So my thesis is based on two fundamental ideas about the market:

The market trades in a range far more than it channels. I believe that the market is primarily range-bound ... until it isn't. Then it channels and finds a new range, and the returns to being range-bound. This idea leads to two important concepts in how I trade:

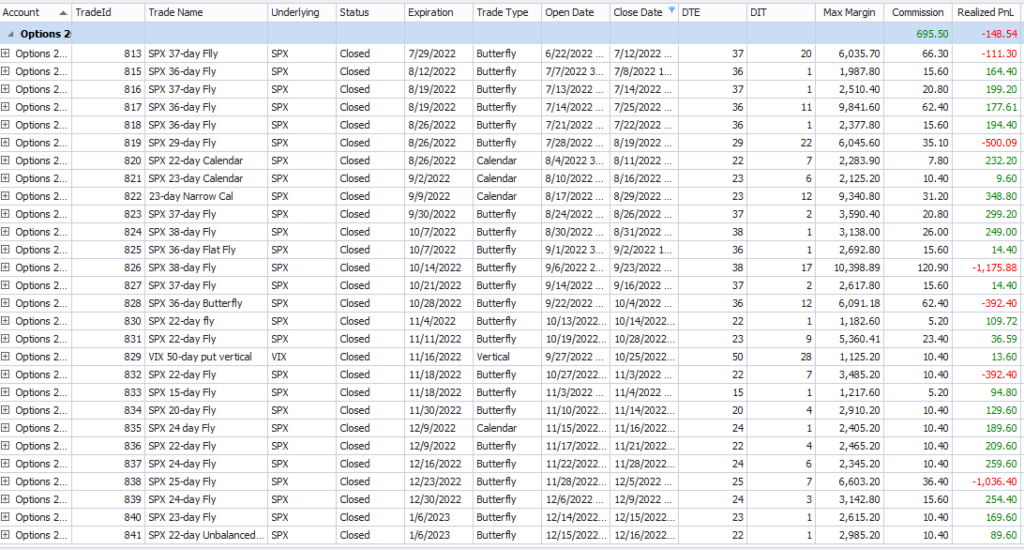

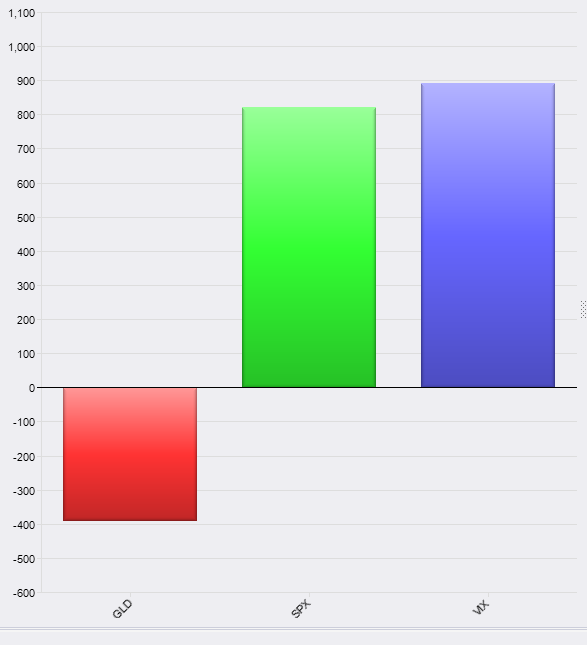

- I trade options on the broad market rather than individual stocks. This means most of the time I trade a big index like SPX, occasionally a volatility index based on the S&P 500 like VIX, and very rarely individual stocks.

- My trades are range-bound. I trade non-directional and my trades do well when the market isn't channeling in one direction or another but rather moves back and forth in a range. This makes things more difficult during those times when the market is channeling but I work those trades and generally lower my capital at risk until a new range is found.

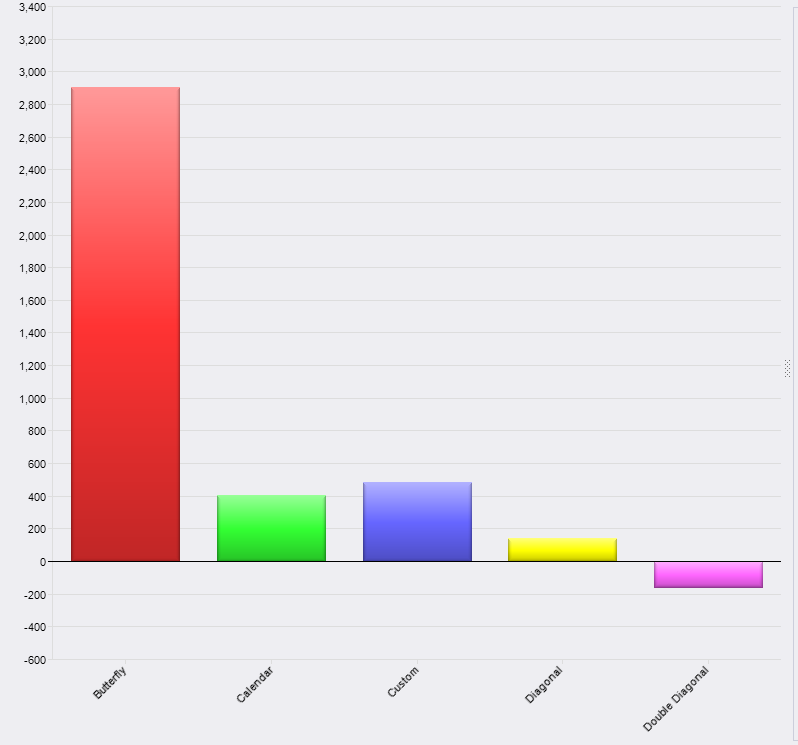

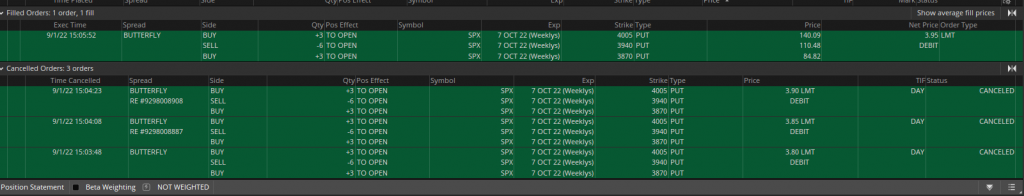

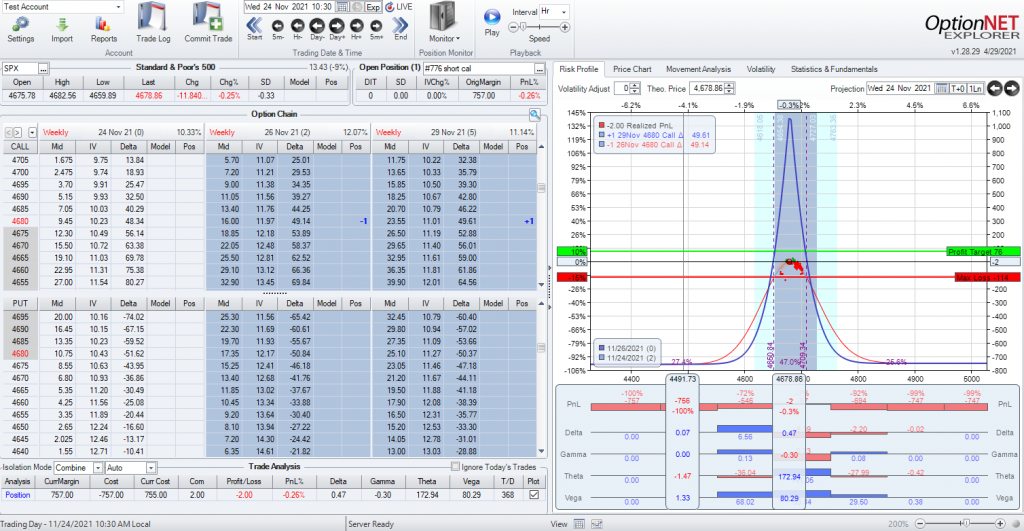

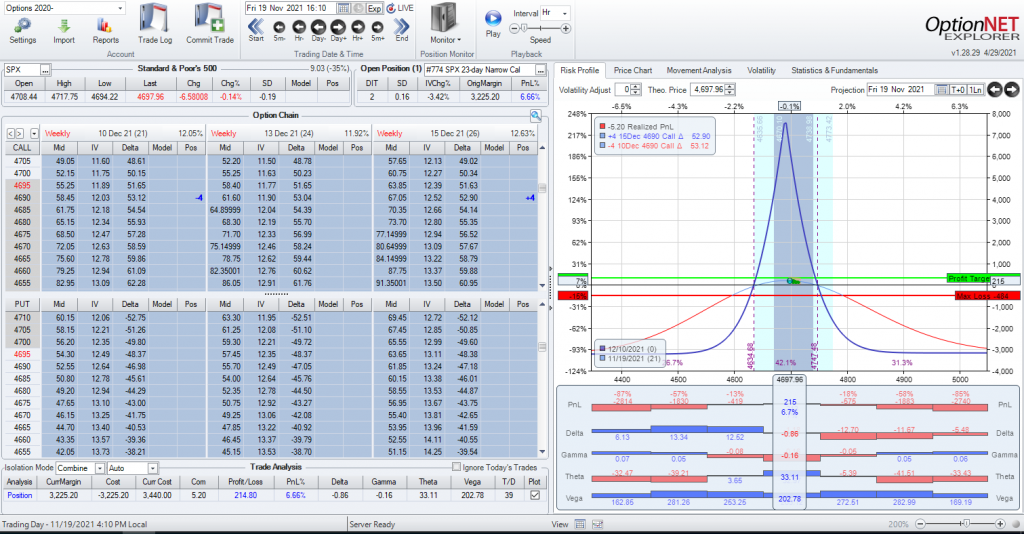

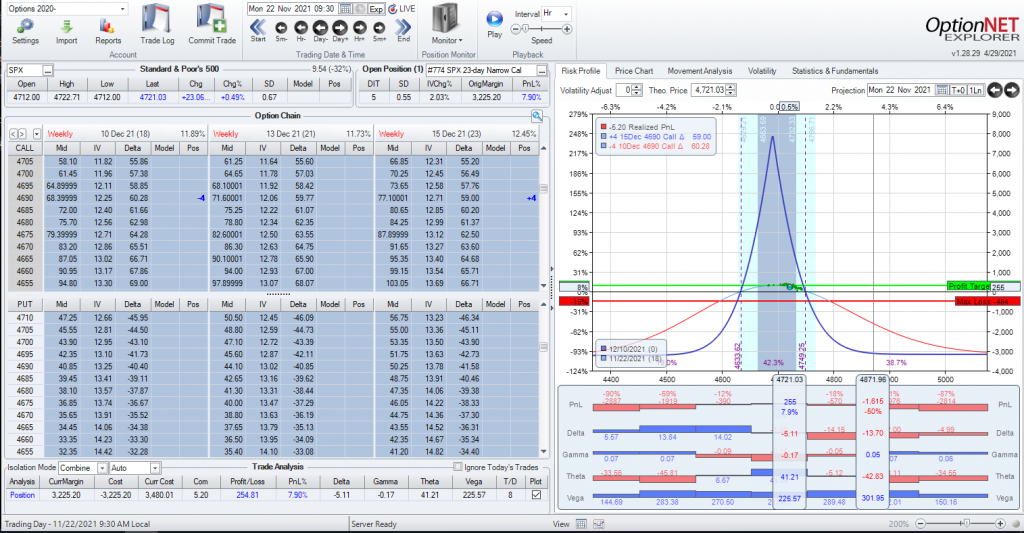

Volatility is mean-reverting. Because I believe this, I pick my trades in a contrarian manner to the current volatility. I typically use VIX as a guide to the volatility of SPX. Is this perfect? No, but it's been a pretty good and simple guide as to the current volatility of SPX. So I pay attention to the volatility range. When it's on the higher end, I go short vega and when it's on the lower end, I go long vega. In the middle, I either pick one or do a bit of both and hedge my bets. This affects which trades I do with SPX. I have long and short vega trades (mostly calendars/diagonals on the long side and butterflies on the short side).

As you can see, these two simple concepts form my trading thesis. And my trading thesis determines what I trade and how I trade it at any given time. Are there exceptions? Sure, but they are exceptions which means they are rare and much smaller than my usual trades. They can be because of highly unusual market conditions or just experiments. But the vast majority of my risk and the bulk of my earnings come from trades based on my trading plan. Trading is a business. Every business makes money by having something they can do over and over to make money. To be consistent, that something has to be repeatable and trading is no different.

Building a Trade Plan

I am a firm believer in a formal trade plan for every trade. I do not put any money into a trade that does not have a complete trade plan because doing so leads to sloppy execution. Time matters in trading and in order to execute properly and timely, you need to know what you are supposed to do. That's not to say that a plan can't change over time, but it shouldn't change mid-trade. If you feel it's best to tweak a trade plan that should be done in between trades. Changing a trade plan in trade is another way to have sloppy execution which can lead to ugly losses. The tricky part is that it will work sometimes which can lead to a false sense of security but, in my experience, when it fails, it fails badly and that leads to inconsistent trading.

So what's in a good, complete trade plan? Here is a summary of the components. For a longer discussion see my blog post on the topic.

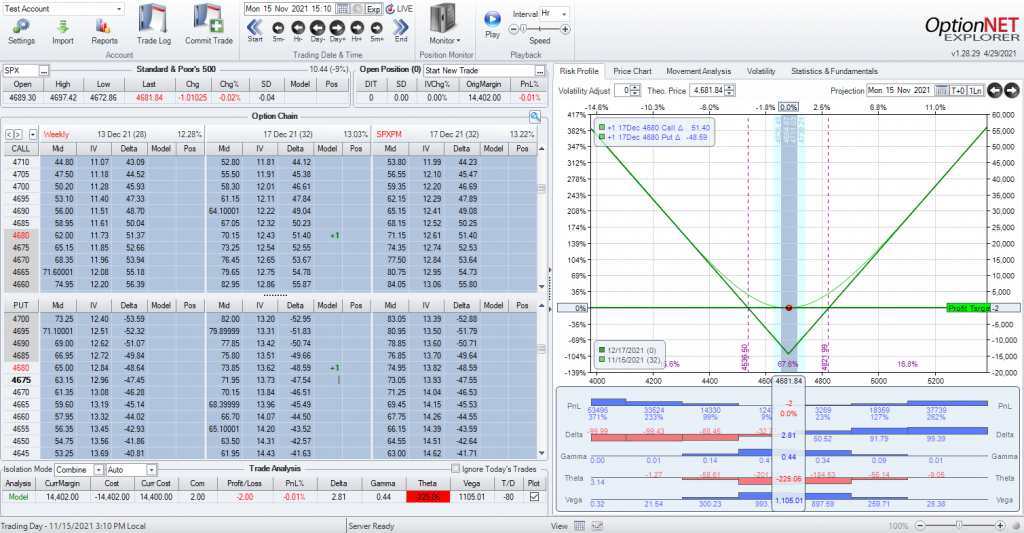

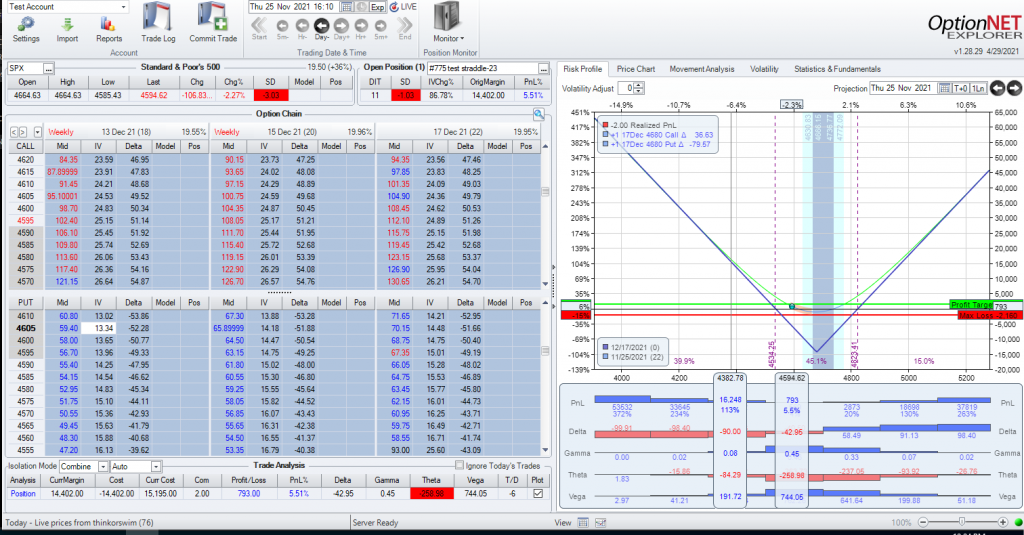

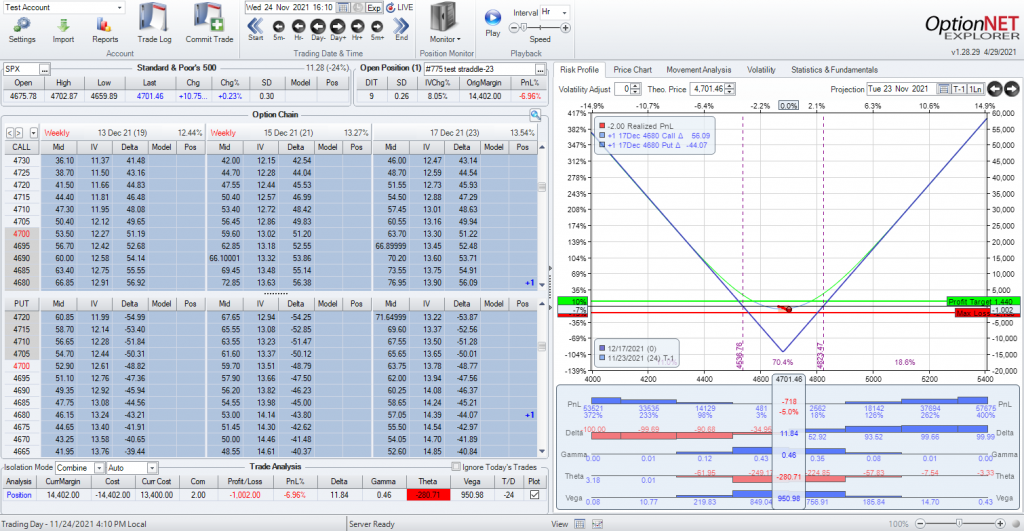

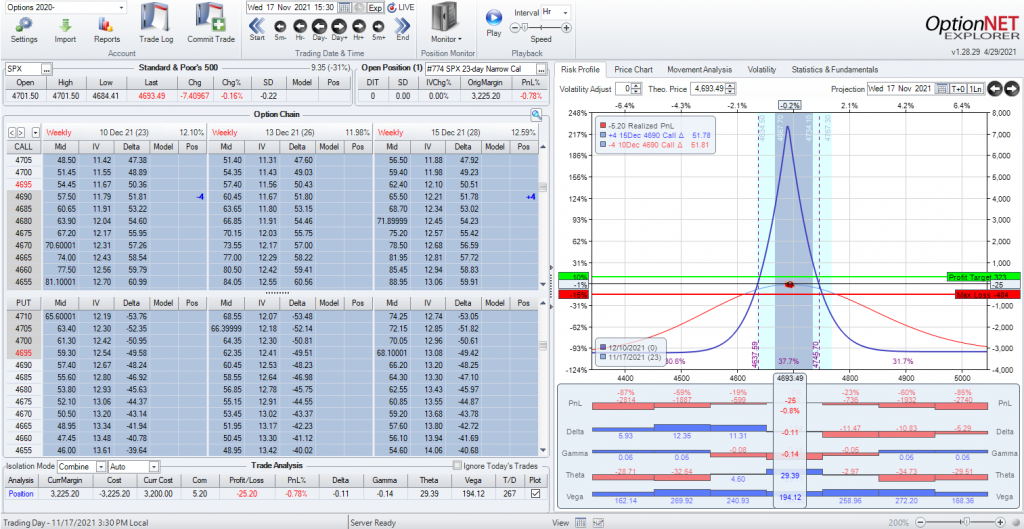

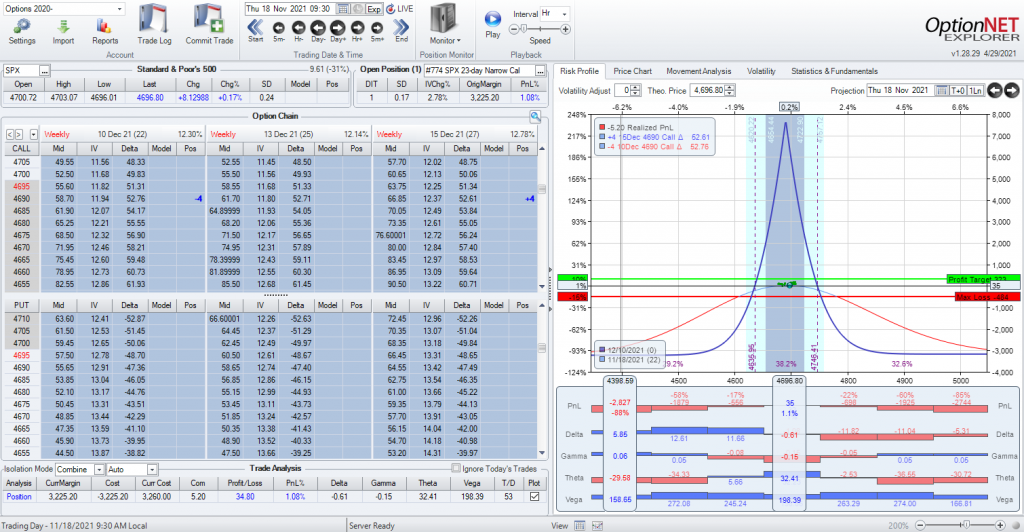

The Setup. What is the trade? Where do I put my strikes? At what expirations? These needs to be formally defined but they can be defined in relative terms (e.g. sell shorts between X and Y points above the money, between A and B days to expiration). Also included in the setup are the conditions under which this trade should be put on. It's likely that there are certain market conditions that are better for one trade than another. If that's the case, those conditions should be formally defined.

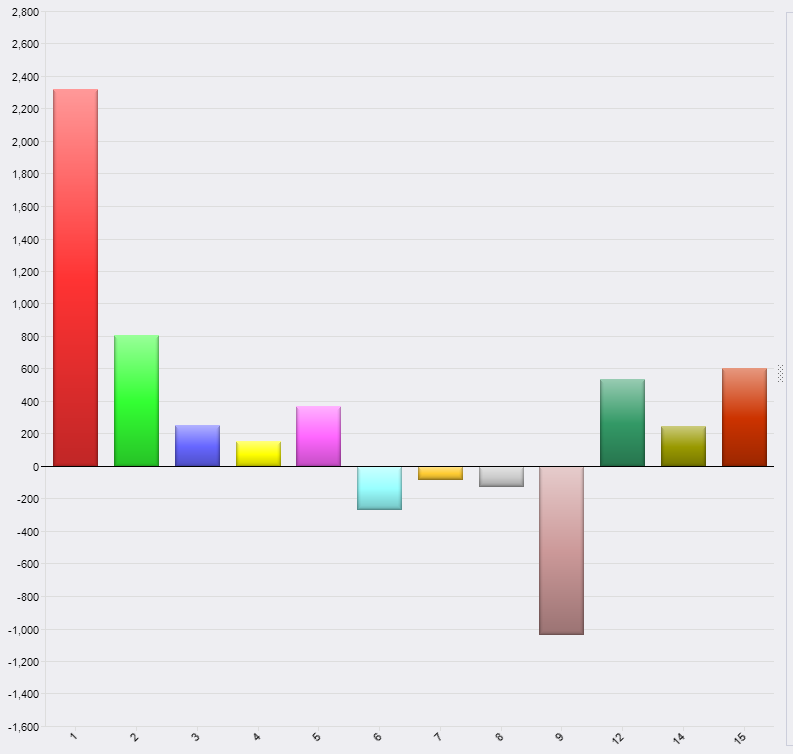

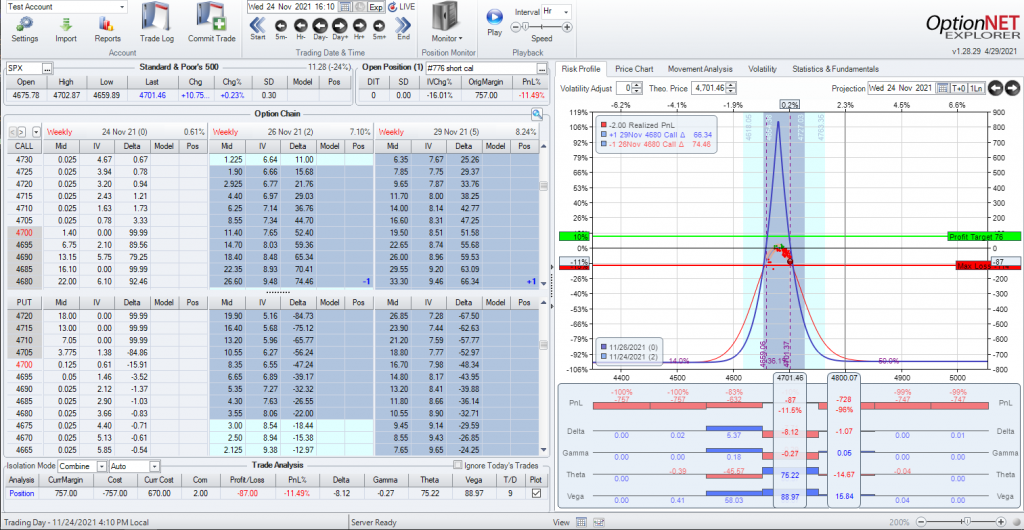

Target Profit. This is a simple idea but one that I see newer traders miss frequently. Trades should be deliberate and that includes a profit goal. It should be specific, either a dollar amount, but more likely a percentage of the risk of the trade. This can be a range (e.g. 10-15%), but it should be specific enough that you will be able to have a limit order in to close at that profit at all times. I am a big believer in limit orders in general, but especially for closing for my profit target. Does this mean I may miss some possible profits? Yes. But it also has helped me capture a price that was only available for a few moments. Some of the biggest mistakes I see here are: “I'll just see what I can get” or “I want the maximum possible profit on this trade”. Remember, you are looking for repeatable processes to make consistent money, not chasing long shots. If you must try a long shot, let them be exceptions that follow the rules of exceptions that I put up above. Speculation is ok if you feel you want to try it, but it should be a very small part of your risk.

Maximum Loss. This is a tough one but also very important. Any trade can lose and you will take losses as they are a normal part of this business. It's important to have a maximum loss to know when to move on to the next trade. The biggest cause of inconsistency is not respecting a max loss. It's very easy to let a losing trade run because you think (hope?) it will come back. Whenever I've taken a bad loss, this is usually what I've done. Generally my max loss is a bit higher than my target profit on a percentage basis. This is to allow a trade to work over time. For example, if my goal is 8-10% profit, I will likely have a 12-15% max loss. In addition to a specific target, a max loss can also include a time limit. I rarely take trades all the way to expiration day and usually don't take them into expiration week.

Adjustments. This is an area to cover what else you may do when not closing the trade for a profit or loss. Some trades may not have adjustments, but some might. From the above we know the conditions when we will close the trade entirely, but what if it gets in trouble and it's worth tweaking it to buy more time for it to succeed. Again, I won't go into heavy detail here as my blog post covers this in detail and there's no need to repeat it all here.

So the combination of all of these parts of a trade plan will tell you what you should do regardless of what happens to the trade. Everything should be covered here. If it isn't, then you need to close the trade and re-work your plan until it does. Don't be the guy who is posting to an Internet forum asking what to do with a trade while it's still on. This is not a winning strategy. If you do want to discuss a trade on such a forum do it either before you put the trade on or after as a post-mortem review.

Execution

So now you have a plan, the next step is execution. This should be the easy part but I think you'll be surprised to discover how hard it can be. As the famous boxer Mike Tyson is famous for saying: “Everyone has a plan until he gets hit in the face” and this is true in trading as well. At first, I recommend being as mechanical as possible. At the end of the day, this is a craft and so you will eventually get a feel for the right time to act on a trade. Over time it will become natural to you, especially if you trade the same underlying for a long time. But before you do that, it's good to learn the discipline of executing your trade plan precisely. For a longer discussion of this see my blog post “Pets vs Cattle”. Learning to be dispassionate about an individual trade and see it as part of a bigger picture is really difficult but very valuable to consistent trading. I advise you to look at that post to see why I think it's so important.

The Aftermath

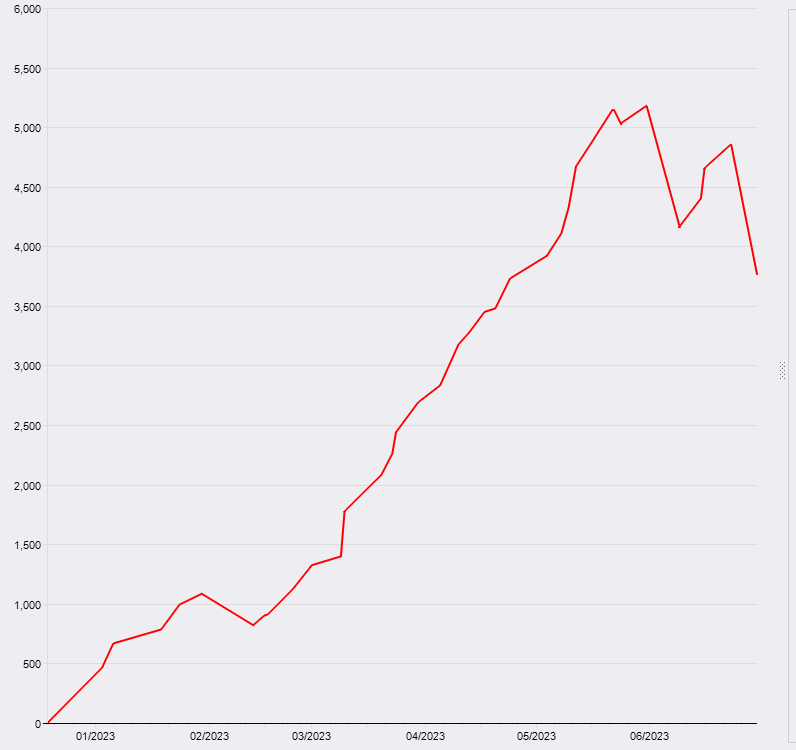

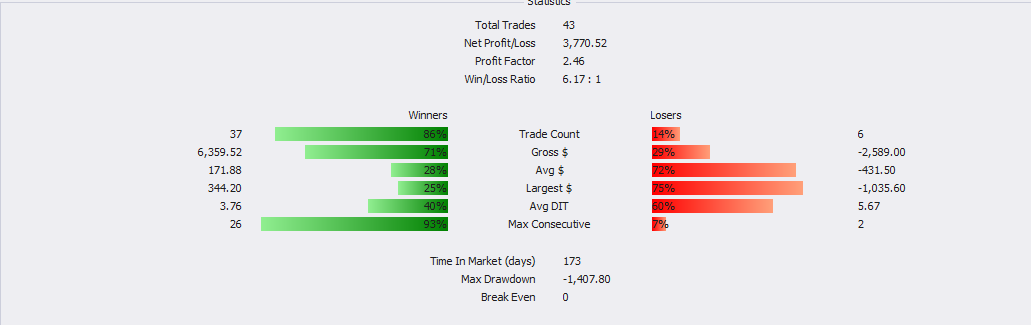

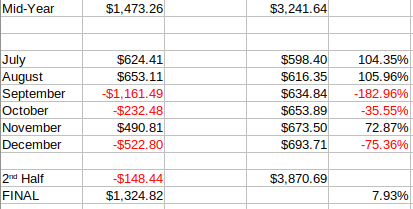

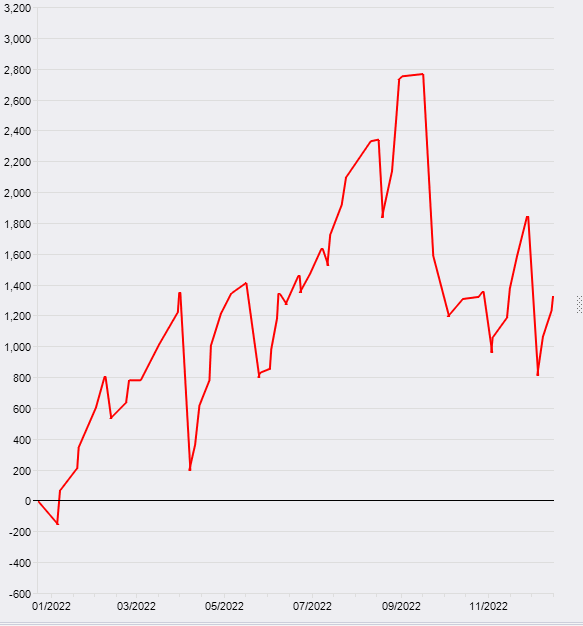

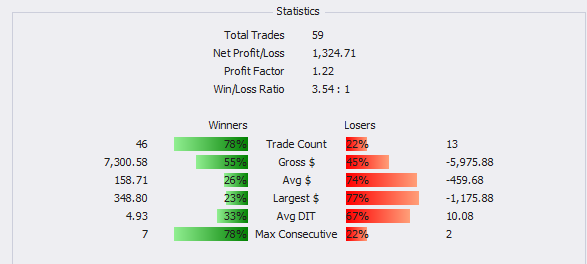

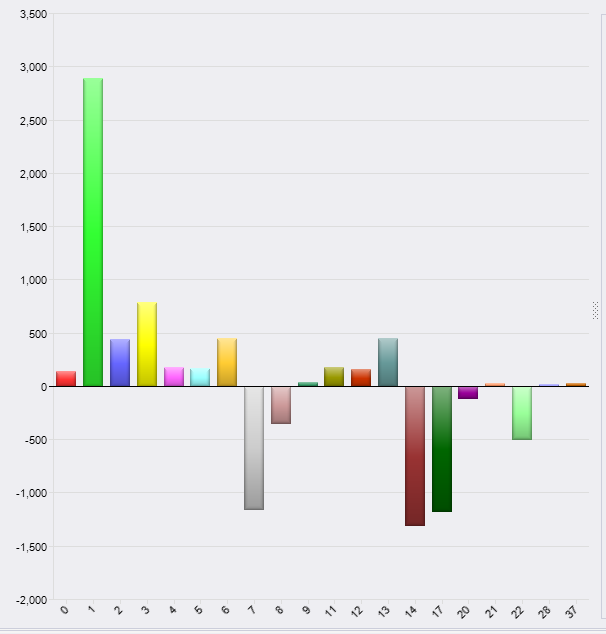

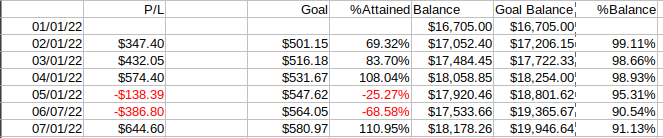

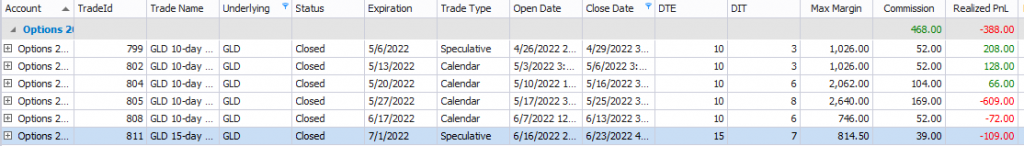

Ok, so the trade is done. Now what? As I've said before, this is a business and like any business it's important to do regular business reviews to learn from your successes as well as your failures, to learn what's working and what is not. It may seem silly but I review every trade on a weekly basis, and then do monthly and semi-annual higher level reviews on my trades here on this site. Making your reviews public certainly isn't mandatory, but it works for me as I will explain in the next section. But I believe that part of being consistent is to learn from what you've done: the good, the bad, and the ugly. If you want this to be a business, you must treat it like a business and any business has to know what they are doing in order to try to do things better. You are welcome to use my reviews as a blueprint for yours, but what's more important is that you formally review every trade and document that review. The act of doing so helps to cement the ideas. You should have lessons for at least some of the time periods. I come up with lessons at the monthly and bi-annual reviews as part of the higher level reviews while the weekly reviews are more down in the details of each trade. But you will need to find out what works for you.

Accountability

Last, but certainly not least is accountability. This has been a game changer for my trading. I consider it second only to Pets vs Cattle in terms of impacting my trading. Trading can be a very solitary activity. It's just you and a screen. It's easy to talk yourself into all sorts of crazy things, many of which aren't good. This is where finding some external accountability comes into play. This can be a trading buddy, a trading group, a mentor, etc. I have had a few mentors over the years and meeting with them really helped me trade better because I knew I had to explain myself at some point. I'm still part of a weekly trade group that I join when my schedule allows. When I stopped regular mentoring sessions, I came up with posting my results online as a way to simulate that accountability. Even though I may never meet anyone who watches my reviews, every trade I do is out there and I record my review of every trade every week and put it out on the Internet. Even if no one actually watches it, I still forced myself to explain what I did, why I did it, and what I learned from it. This is why I do what I do here online. Yes, I enjoy sharing what I do, talking about trading and, sometimes, helping people but I get value out of the act of publishing my results. It helps keep me grounded and has made me a better trader. I've been doing this for over 4 years now and my trading has definitely improved more over that that time than before. Yes, some of that is experience but I firmly believe some of it comes from anonymous accountability. I can't tell you exactly how to do this, but I hope I have given you some ideas.

In conclusion, I hope this post helps some other traders out there who are learning this craft. Becoming consistent is not easy and, from what I've seen online, many others struggle with it as well. So I wanted to put out my thoughts on this in a longer form than would make sense on most online forums. As always, feel free to reach out with any questions, comments, ideas, etc. I enjoy talking about trading with people who “get” this stuff.

This content is free to use and copy with attribution under a creative commons license.