Why I Don't Like Iron Condors

Originally posted on April 4, 2021

It’s certainly been a while since I’ve posted here but I like to post when I find topics that I think are relevant to what I’m seeing in the various trading communities with which I’m involved, including this one. I do put a good amount of time and effort into these posts and so I want them to be useful to other traders.

That being said, the point of the title is not to be click bait, I swear. I’m not here to say that Iron Condors are a bad trade or that there aren’t traders out there who make money with them. Those traders exist and more power to them. This is very much an opinion piece as to why I don’t like them and what I think new traders need to understand before putting them on. The inspiration for this blog is that several newer traders have reached out to me talking about wanting to do Iron Condors. I understand why. When you look at the risk graph, they look like one of the safest plays out there. Those wide break evens are a siren’s song to new traders. But none of this is to say that there are not strategies to handle the risks of this trade. Just about any trade can work with a solid plan and good execution. But I think it’s critical to understand this trade before jumping into one.

What is an Iron Condor?

Two simple ways to look at the structure of an Iron Condor are:

- Two out of the money credit spreads

- A hedged strangle

The width of the spreads is up to you, but the idea is that if the underlying stays roughly between the two shorts, by expiration, the trade wins. If not, the trade loses. So the biggest risk is a large move in the underlying. Typically the shorts are far out of the money and so this gives the underlying a lot of room to move while getting a net credit when the trade is put on. As these are credit spreads, the maximum gain is the credit received and the risk of the IC is the width of the spreads minus the credit received. If you aren’t familiar with credit spreads, I advise you learn about them before even looking at an Iron Condor.

The Appeal of an Iron Condor

Why do traders like Iron Condors? Primarily, it’s the room they can provide. You can put those spreads out as wide as you like. This can greatly increase your probability of success at expiration. It’s relatively simple to set up an Iron Condor that has a 90% probability of success at expiration. This “safety” is what I think lures new traders to this trade. Why not put on a trade that should almost always win? Those odds sound really good. And when they see the risk graph at the start of the trade it looks like a trade that you an pretty much set and forget. Easy money, right?

The Risks of an Iron Condor

As I stated earlier the primary risk of an Iron Condor is that the underlying moves beyond one of the short strikes. At expiration this would result in the maximum loss for the trade. Of course, you are not required to stay in the trade until expiration (in fact, I almost never do) and there are adjustment strategies that can help trades that are moving too far in either direction for comfort.

Risk/Reward

So, why does this trade look too good to be true? Why isn’t everyone doing Iron Condors? Who wouldn’t like a trade that can win 90%+ of the time? And this is on one of the reasons I don’t like Iron Condors or, more specifically, wide Iron Condors. As the two spreads get further apart, the trade gets more room to work and the probabilities get better, but the reward also drops while the risk really does not. This is because far out of the money options contracts have less premium to sell while the difference in the premiums based on the width of each spread doesn’t change much, certainly not in proportion to the drop in premium. And the net credit is the maximum reward of the trade. The best case for this trade is that all of the contracts expire worthless and you are left with the credit received. But the further out you sell the spreads to get more room, the less premium you collect. This can lead to pretty low returns which vs the risk of the trade.

Example: A High Probability Iron Condor

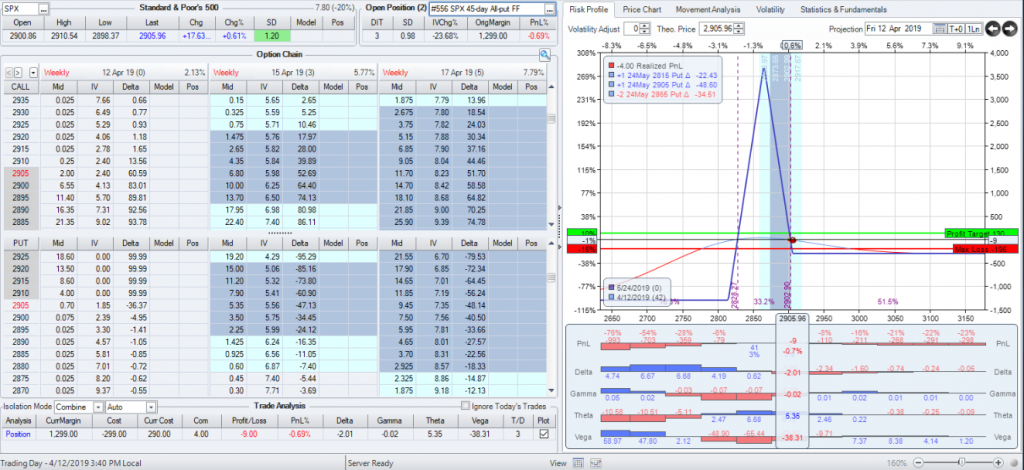

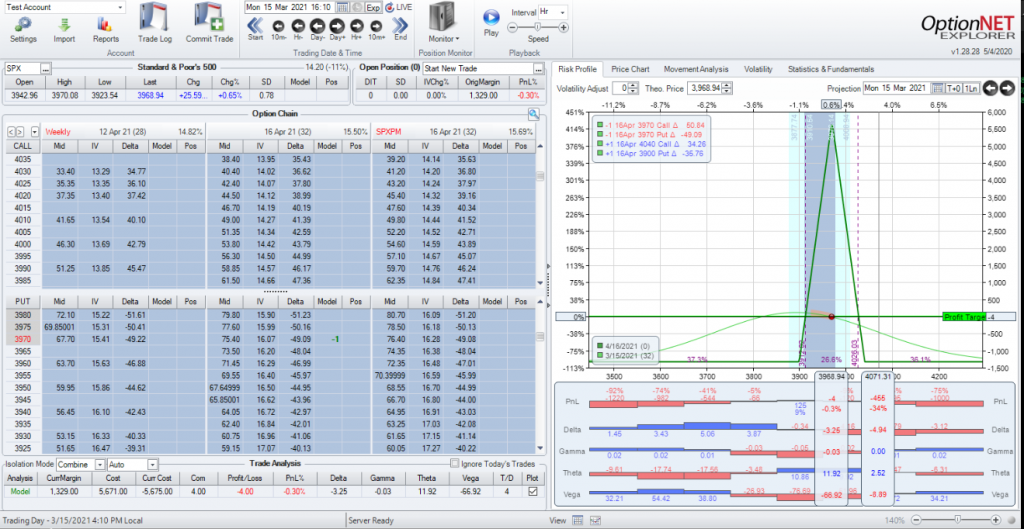

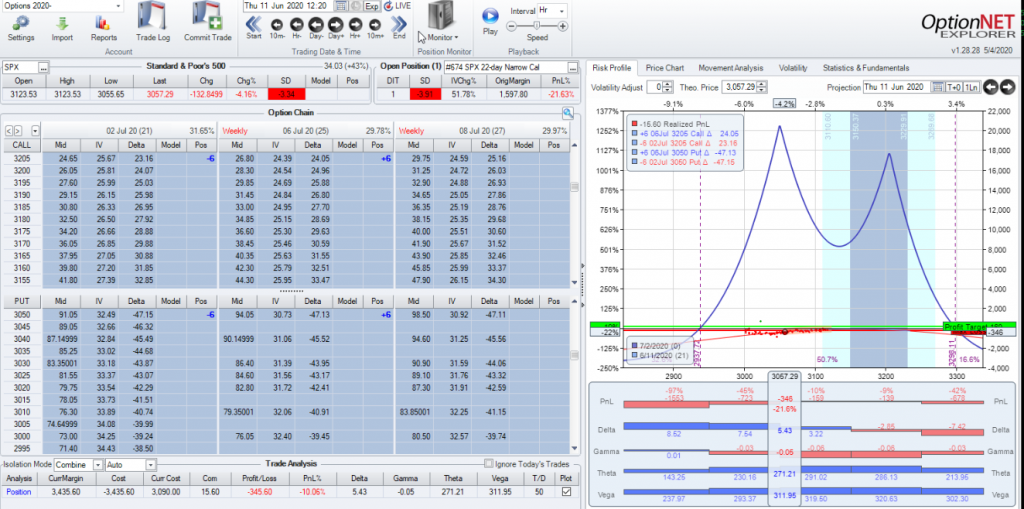

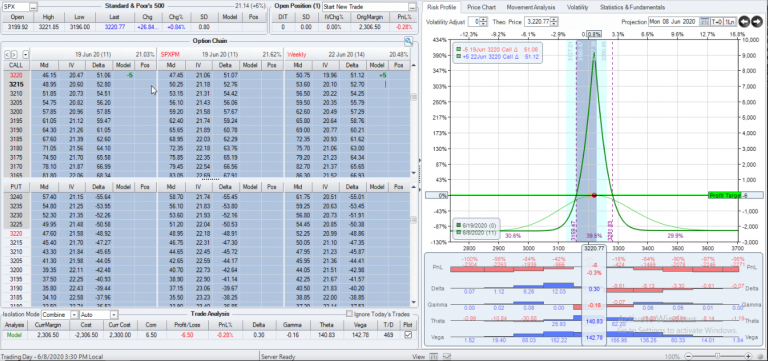

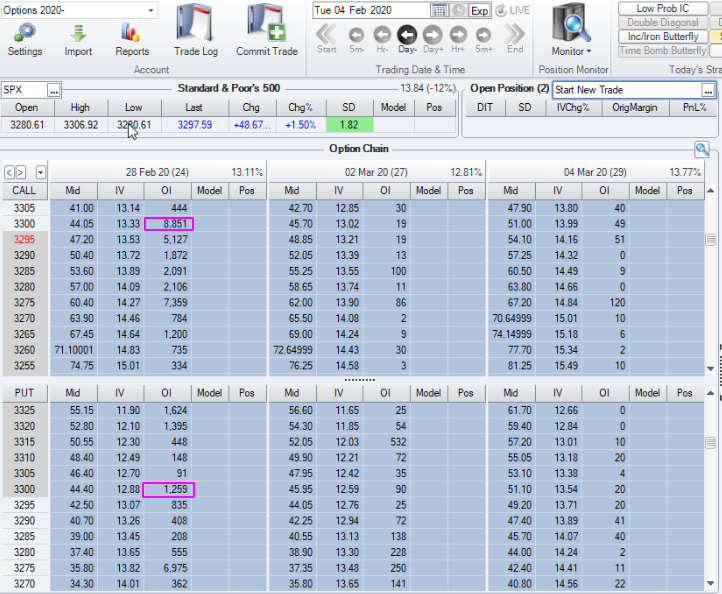

Let’s look at some real-world examples to try and make this clear. Here is an example of what I would consider to be a high probability IC:

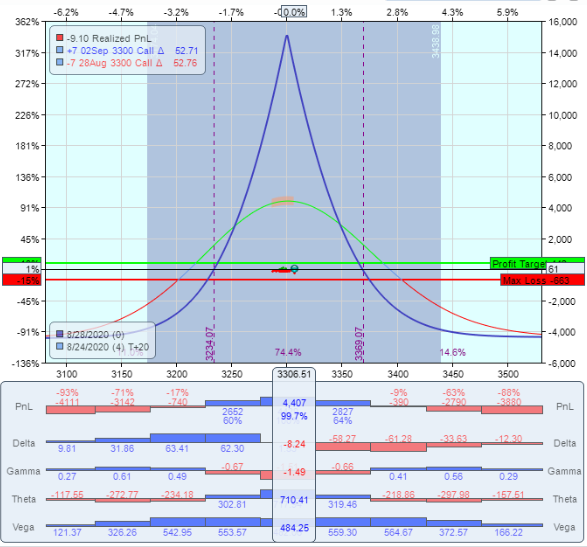

In this trade, the shorts are opened at around a .10 delta on each side, and the spreads are 5 points wide. This yields a probability of success at expiration of nearly 90%. The net credit of this 3-lot is $198 which the most that it can make (note: this is after commissions of $12. If your platform does not charge commissions, you could get $210 but my point will still stand). But the total risk on this trade is $1302. So you are risking $1300 to make no more than $200 (using rounded figures). That’s over 6x the risk compared to the reward. And, remember to get that full credit, I have to go to expiration (which my readers will know, I don’t like to do, as the price risk can get crazy). In addition to far out of the money options having low premium, the theta is also low. So for this trade, my starting theta for this trade is less than $7/day. Theta is a big component of making money in this trade since I want both spreads to decay as quickly as possible. The range of this trade is very nice with about 200 points on the upside and 350 points on the downside. But it’s a 30-day trade. Given this past year, do you think those kind of moves could happen over the next 30 days? Iron Condors are negative Vega trades so traders prefer to open them when volatility is high because a vol drop helps the trade and with higher volatility comes higher premiums overall. But when volatility is high, the underlying tends to move more so there’s added risk.

Something else to consider with Iron Condors is how fast the trades can get into trouble. With those near vertical sides, as the underlying moves out towards the shorts, the delta and gamma tend to increase and the trade starts to become directional which is exactly the opposite of what you wanted when you put this trade on. If you want to pick direction, just put on a single credit spread and only take risk on one side. So while the Iron Condor gives you a lot of room on the expiration graph, let’s see what the curves look like 2 weeks later.

The slope is starting to get steeper as you move towards the edges, especially on the upside. This means that if SPX moves in that direction, you will become more directional as delta and gamma increase and each move up hurts the trade more. The downside certainly looks better but keep in mind as well that a sharp move to the downside will spike volatility and so the curve won’t be quite a generous ad the graph currently shows. So if you let the trade go to either side, you may have some white knuckles while you are holding on. Alternatively, you can adjust but most of these adjustments reduce the total credit of the trade which, in turn, lowers the amount of the win. If you over-adjust this, you may end up with no credit left and, at that point, the trade will just lose.

The slope is starting to get steeper as you move towards the edges, especially on the upside. This means that if SPX moves in that direction, you will become more directional as delta and gamma increase and each move up hurts the trade more. The downside certainly looks better but keep in mind as well that a sharp move to the downside will spike volatility and so the curve won’t be quite a generous ad the graph currently shows. So if you let the trade go to either side, you may have some white knuckles while you are holding on. Alternatively, you can adjust but most of these adjustments reduce the total credit of the trade which, in turn, lowers the amount of the win. If you over-adjust this, you may end up with no credit left and, at that point, the trade will just lose.

The most I can make on this trade is about 15% but I can’t get that until expiration. If I go to expiration and lose, I will lose $1300. I’m just not happy with the risk/reward ratio on this as well as the glacial speed of time decay.

Example: A Lower Probability Iron Condor

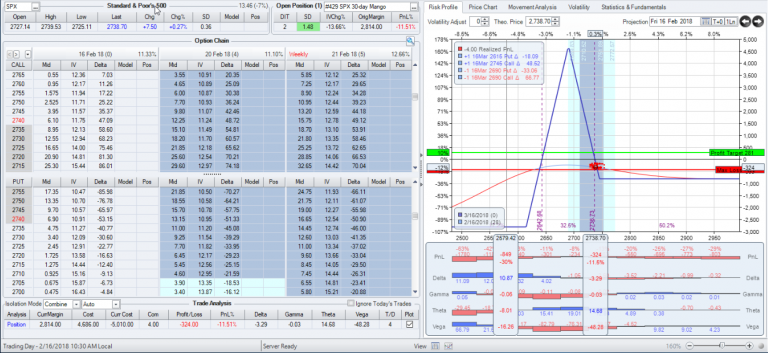

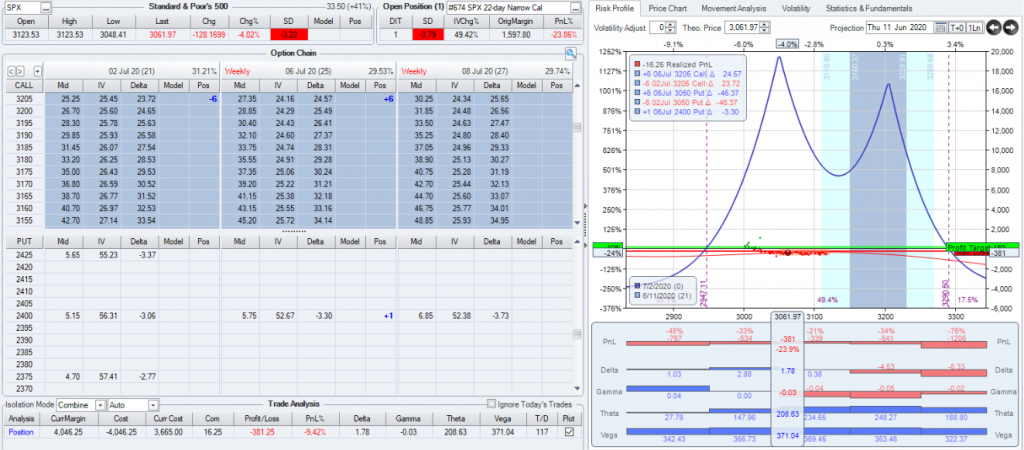

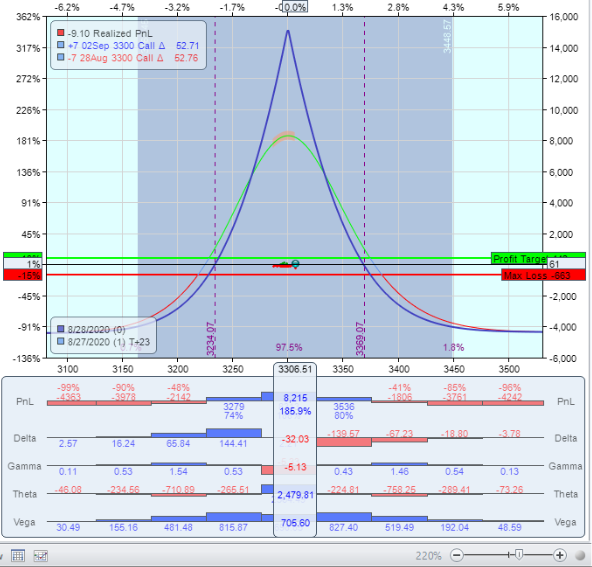

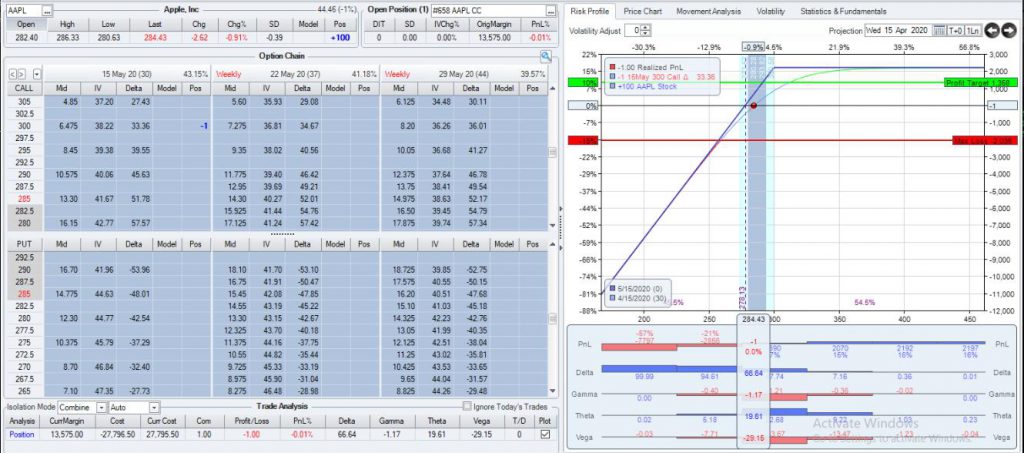

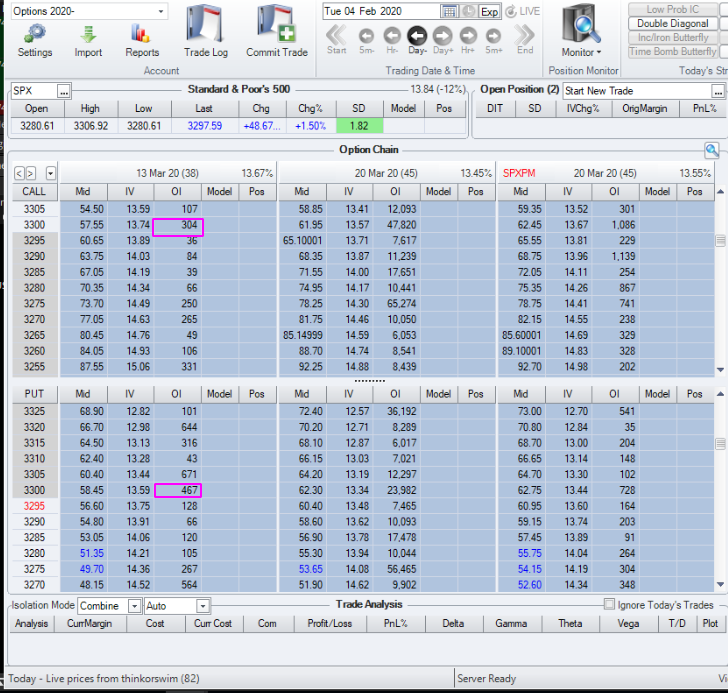

It is, of course possible to sell higher deltas. If I do this, I take in more premium, and get higher theta decay. What I lose is the room to move. Take a look at this example:

In this trade, I’m selling around a .20 delta on each side. In this case I sold a 4-lot to try and keep the risk close to the other trade. In this case, it’s a bit more at $1356. However, my credit is now $660 (or $644 after my expenses). This puts my risk/reward at about 2x. I certainly like this better. But the downside is my range is now 140 points on the upside and 176 points on the downside. That’s a significant difference and it brings my probability of profit down to about 66%. On the positive side, my theta is better at about $10.50/day at the beginning of the trade. If I had to trade an Iron Condor, I like this better than the first one. However, this puts your risk/reward closer in line with other trades that I like better.

In this trade, I’m selling around a .20 delta on each side. In this case I sold a 4-lot to try and keep the risk close to the other trade. In this case, it’s a bit more at $1356. However, my credit is now $660 (or $644 after my expenses). This puts my risk/reward at about 2x. I certainly like this better. But the downside is my range is now 140 points on the upside and 176 points on the downside. That’s a significant difference and it brings my probability of profit down to about 66%. On the positive side, my theta is better at about $10.50/day at the beginning of the trade. If I had to trade an Iron Condor, I like this better than the first one. However, this puts your risk/reward closer in line with other trades that I like better.

Example: An Iron Butterfly

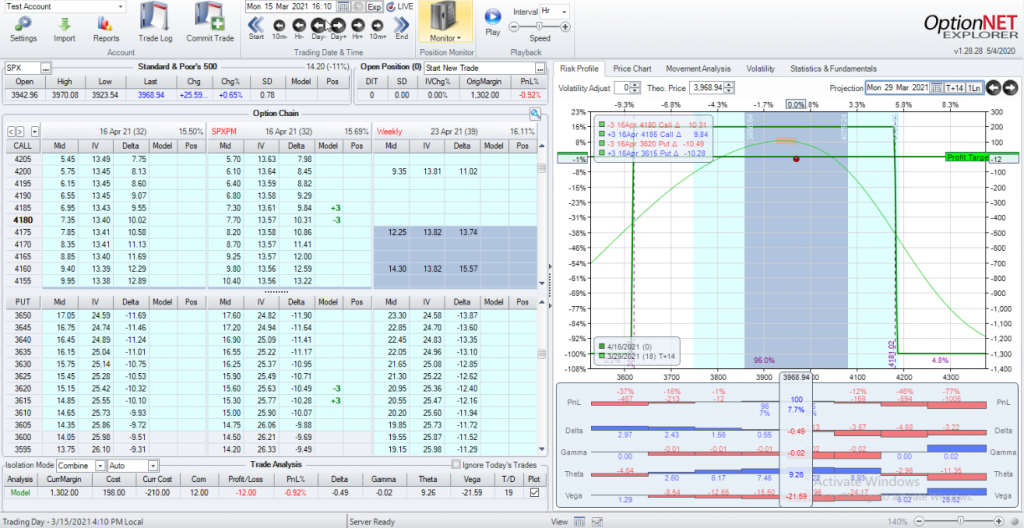

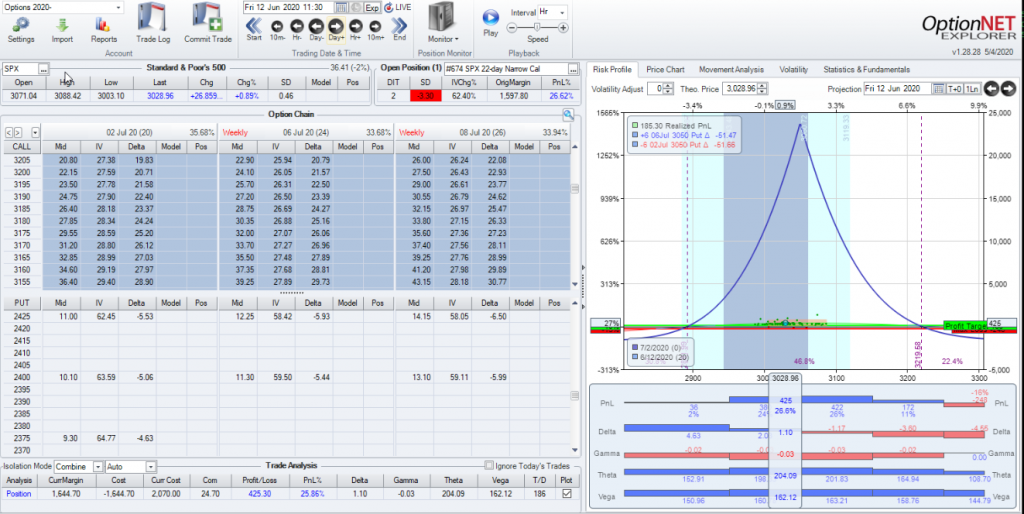

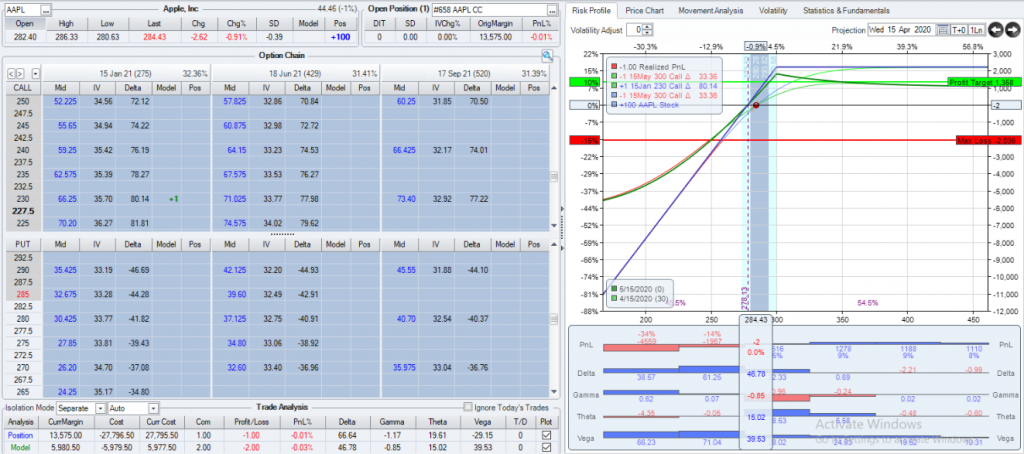

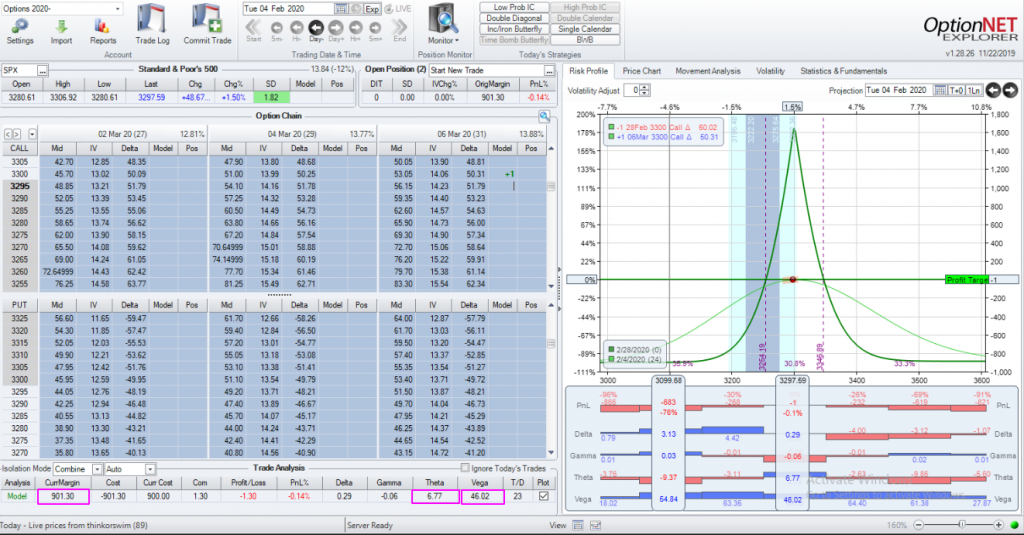

A butterfly is the most extreme condor in terms of width. Both spreads are selling the same short. While I prefer butterflies that are all calls or all puts, I’ll use an Iron Butterfly here because it is more similar to the Iron Condor (both have two credit spreads) so it will compare better to the Iron Condors.

With this trade, my range is very narrow compared to the Iron Condors. And, with this trade, the width of the structure is determined by the width of the spreads themselves rather than the distance between the shorts since that distance is zero. So why do I like this trade better? It’s not the range as, in this case, I have around 70 points in each direction which gives me an expiration probability of about 26%. But, remember, I have no plans on staying to expiration week, yet alone expiration day, so the expiration probabilities don’t mean as much to me. I’m far more concerned with the next week or two. Ideally, I’m out of this trade in 2 weeks or less. My total risk is between the two Iron Condors at about $1330. but I took in $5671 in credit. That flips the risk/reward ratio over to the reward side. Now, with any butterfly, the goal should never be to get the maximum profit as the underlying would have to expire on the exact short strikes which is akin to winning the lottery. But, I’m usually trying to make about 10% on these trades in far less time and having that large total credit gives me plenty of room to reach it, even if I had to reduce the total credit with adjustments. And if I was actively managing an Iron Condor, especially the lower probability example, if the underlying moved 70 points in either direction, I’d probably have adjusted the Iron Condor as well which means the work to maintain each is similar given similar market conditions. I also like the starting Theta of about $12/day even though my total risk is a bit lower than the lower probability Iron Condor.

With this trade, my range is very narrow compared to the Iron Condors. And, with this trade, the width of the structure is determined by the width of the spreads themselves rather than the distance between the shorts since that distance is zero. So why do I like this trade better? It’s not the range as, in this case, I have around 70 points in each direction which gives me an expiration probability of about 26%. But, remember, I have no plans on staying to expiration week, yet alone expiration day, so the expiration probabilities don’t mean as much to me. I’m far more concerned with the next week or two. Ideally, I’m out of this trade in 2 weeks or less. My total risk is between the two Iron Condors at about $1330. but I took in $5671 in credit. That flips the risk/reward ratio over to the reward side. Now, with any butterfly, the goal should never be to get the maximum profit as the underlying would have to expire on the exact short strikes which is akin to winning the lottery. But, I’m usually trying to make about 10% on these trades in far less time and having that large total credit gives me plenty of room to reach it, even if I had to reduce the total credit with adjustments. And if I was actively managing an Iron Condor, especially the lower probability example, if the underlying moved 70 points in either direction, I’d probably have adjusted the Iron Condor as well which means the work to maintain each is similar given similar market conditions. I also like the starting Theta of about $12/day even though my total risk is a bit lower than the lower probability Iron Condor.

So while the butterfly doesn’t look very appealing compared to the Iron Condor in terms of room and expiration probabilities, there are other benefits that help me make money with it.

My goal is not to encourage or discourage you from any particular trade. If you are comfortable with a given trade, have a detailed trading plan, and can execute that plan consistently, any trade can be a good trade. Rather my goal here is to show my preferences and the reasons why I prefer one trade over another. Have questions? Have a trade you really like? Feel free to reach out to me directly.

This content is free to use and copy with attribution under a creative commons license.

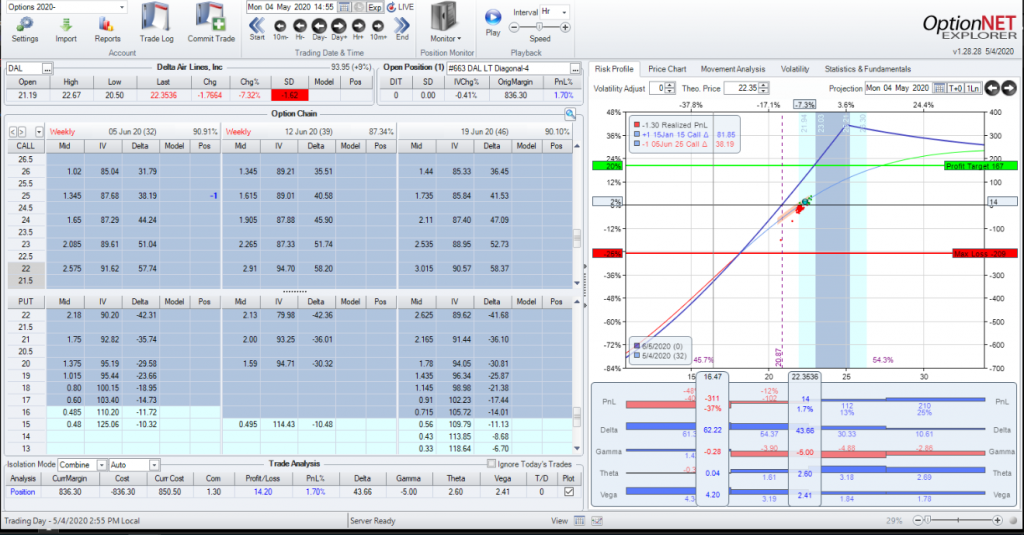

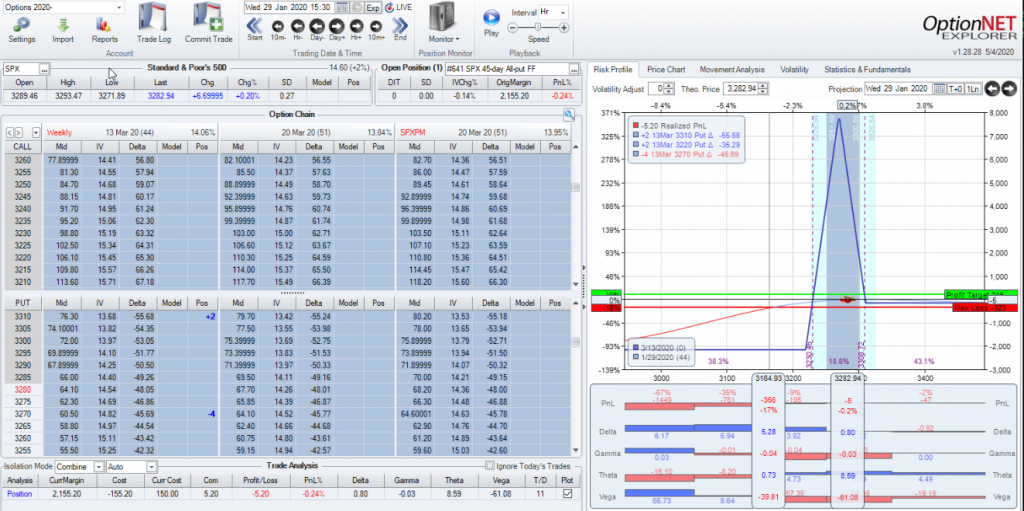

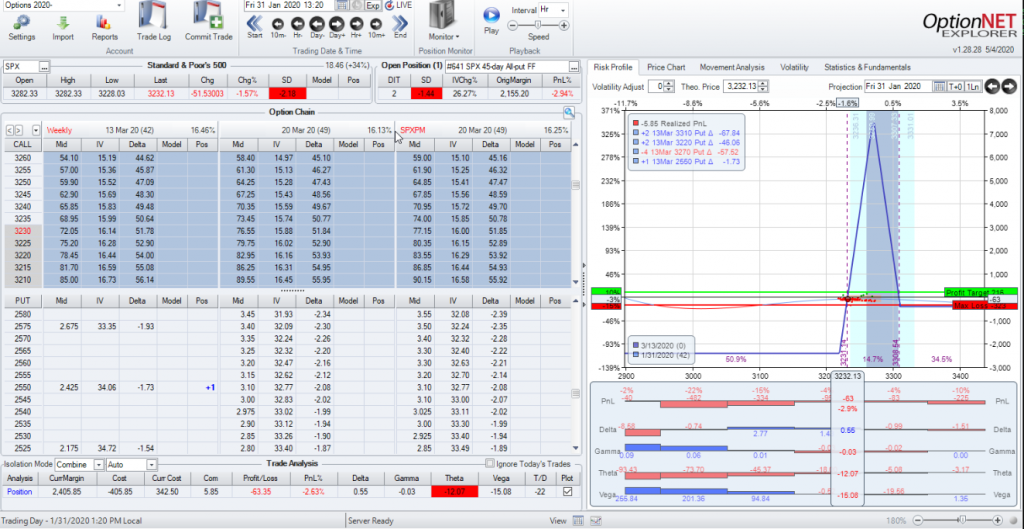

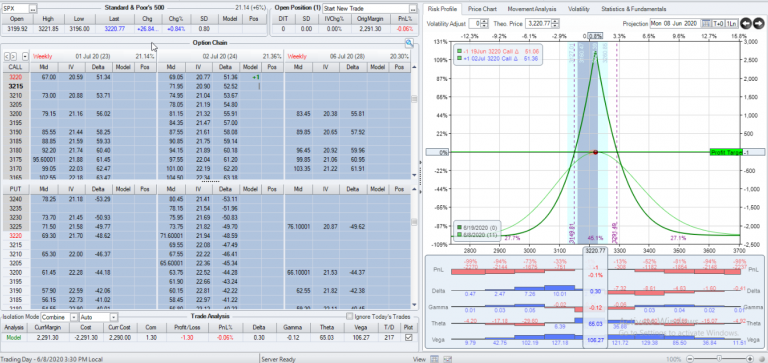

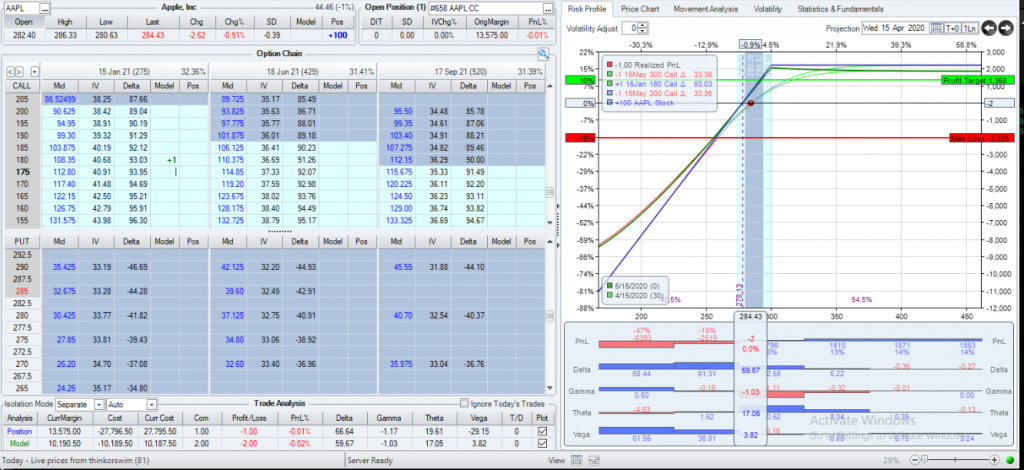

This is a common setup for a butterfly for me. It’s an unbalanced butterfly 44 days out, 40 points up, 50 points down which makes a nice flat delta trade with .80 deltas on a 2-lot. However, 2 days later the trade looked like this:

This is a common setup for a butterfly for me. It’s an unbalanced butterfly 44 days out, 40 points up, 50 points down which makes a nice flat delta trade with .80 deltas on a 2-lot. However, 2 days later the trade looked like this: SPX moved 51 points down in a day which constituted a 2 SD move. My trade is at an adjustment point so instead of trying to buy a lower fly, I add a put:

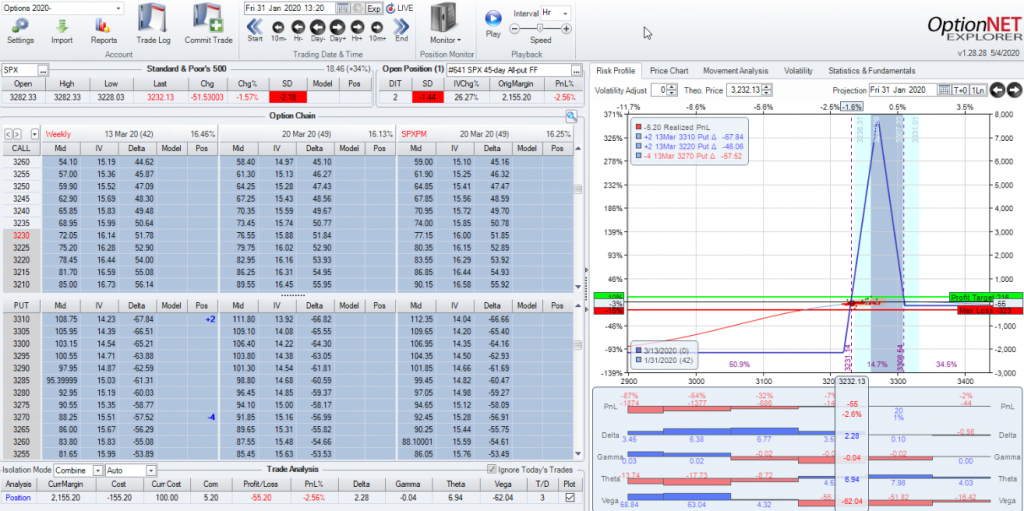

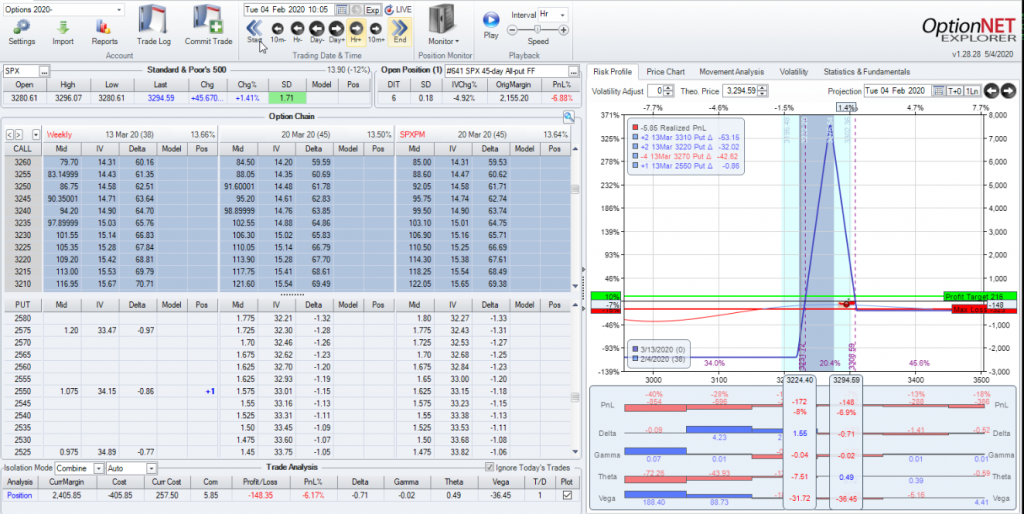

SPX moved 51 points down in a day which constituted a 2 SD move. My trade is at an adjustment point so instead of trying to buy a lower fly, I add a put: I bought a 2550 put (way out of the money). This is because to cut my deltas by about 80% I needed around 1.75 deltas. But now I’m not worried about the trade getting into trouble on the downside and I can wait it out and see what happens given that I’m really flat so that price movement doesn’t scare me. In return for that, my position is negative theta at the moment. While I don’t like that, I’ll take it for now to help stop the delta/gamma bleeding. When I bought the put it had 42 days left in it. That means I’m willing to keep it on for about 8 days before I need to sell it outright or roll it out. This happens to be a Friday so I kept this put on over the weekend and even into the early part of the week. It wasn’t until Tuesday Feb 4 that the trade looked like this:

I bought a 2550 put (way out of the money). This is because to cut my deltas by about 80% I needed around 1.75 deltas. But now I’m not worried about the trade getting into trouble on the downside and I can wait it out and see what happens given that I’m really flat so that price movement doesn’t scare me. In return for that, my position is negative theta at the moment. While I don’t like that, I’ll take it for now to help stop the delta/gamma bleeding. When I bought the put it had 42 days left in it. That means I’m willing to keep it on for about 8 days before I need to sell it outright or roll it out. This happens to be a Friday so I kept this put on over the weekend and even into the early part of the week. It wasn’t until Tuesday Feb 4 that the trade looked like this: Note that we had a big up day that put the stock above the middle of the fly structure. At this point it’s time to sell it off at a loss. I lost a bit over 50% of the value of the put but it was just insurance that wasn’t needed. On the plus side, I didn’t pay much for it and this trade eventually closed for a small win. In perfect hindsight, I could have done nothing and done better but there was no way to know that at the time and it was better from a risk management perspective to buy the put and protect the position so that it did not get out of control and become a big loss.

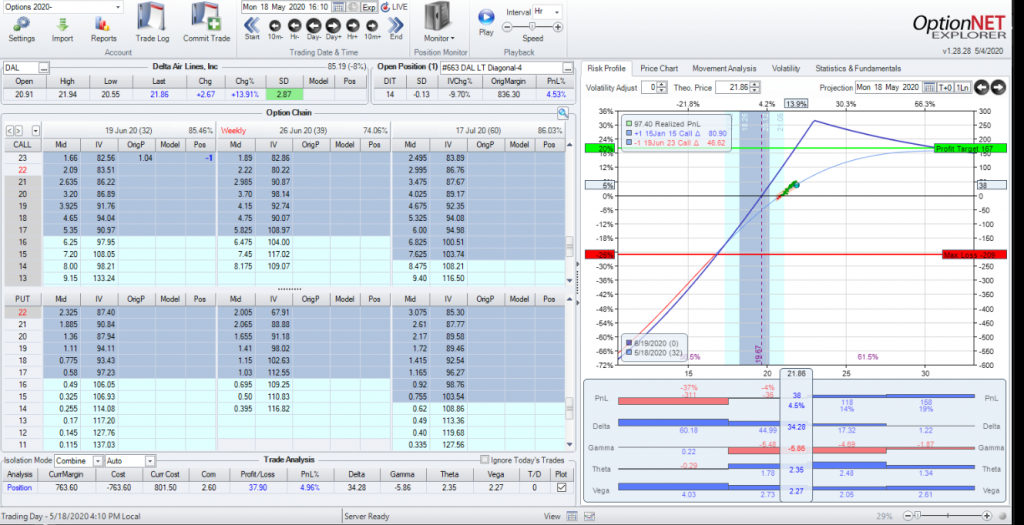

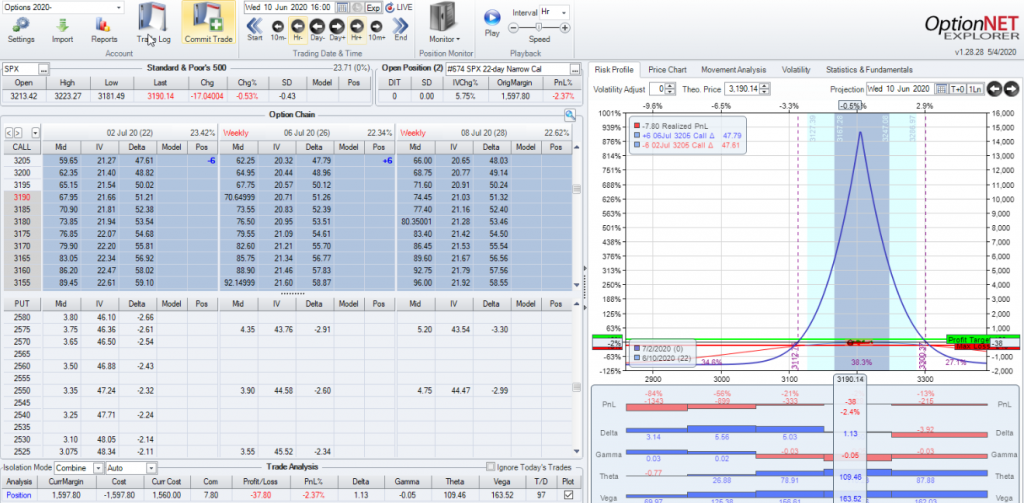

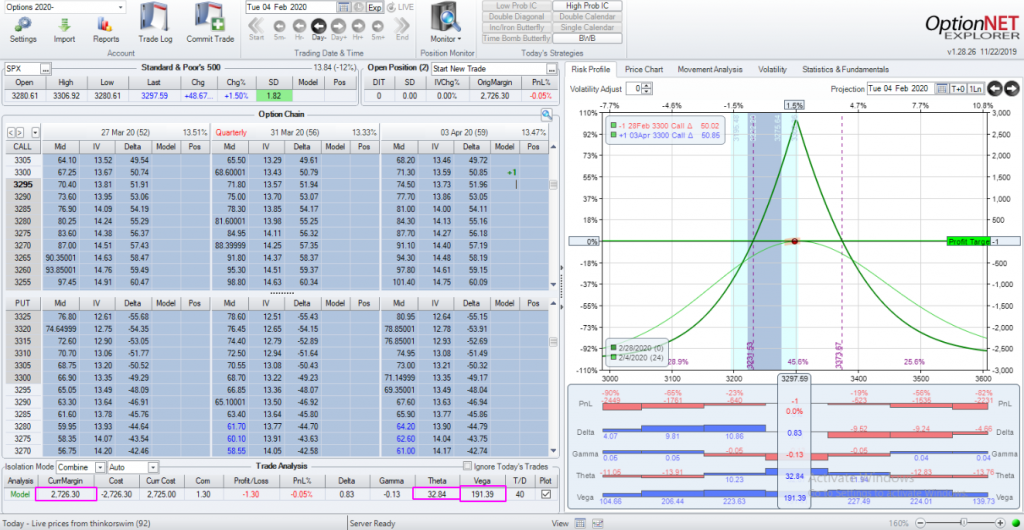

Note that we had a big up day that put the stock above the middle of the fly structure. At this point it’s time to sell it off at a loss. I lost a bit over 50% of the value of the put but it was just insurance that wasn’t needed. On the plus side, I didn’t pay much for it and this trade eventually closed for a small win. In perfect hindsight, I could have done nothing and done better but there was no way to know that at the time and it was better from a risk management perspective to buy the put and protect the position so that it did not get out of control and become a big loss. This is a very typical trade that I put on for much of this year. In the crazy market we’ve had this year, I really like the initial room this trade has and the relatively low vega exposure for a calendar. However, the very next morning I woke up to this:

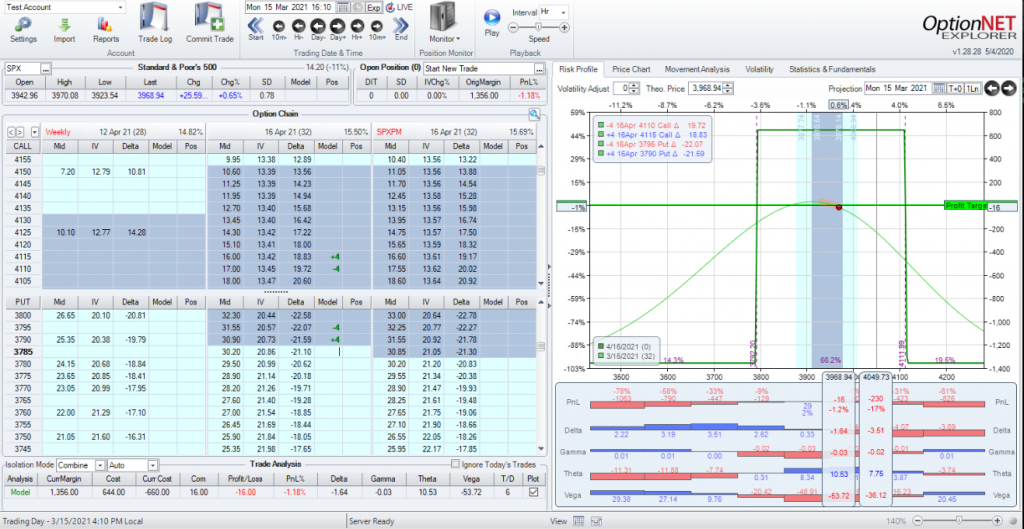

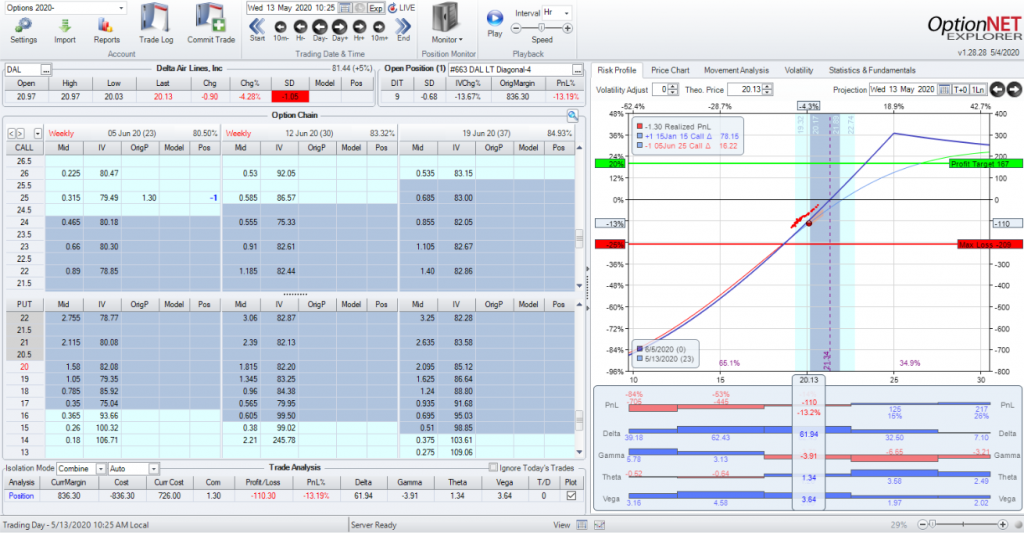

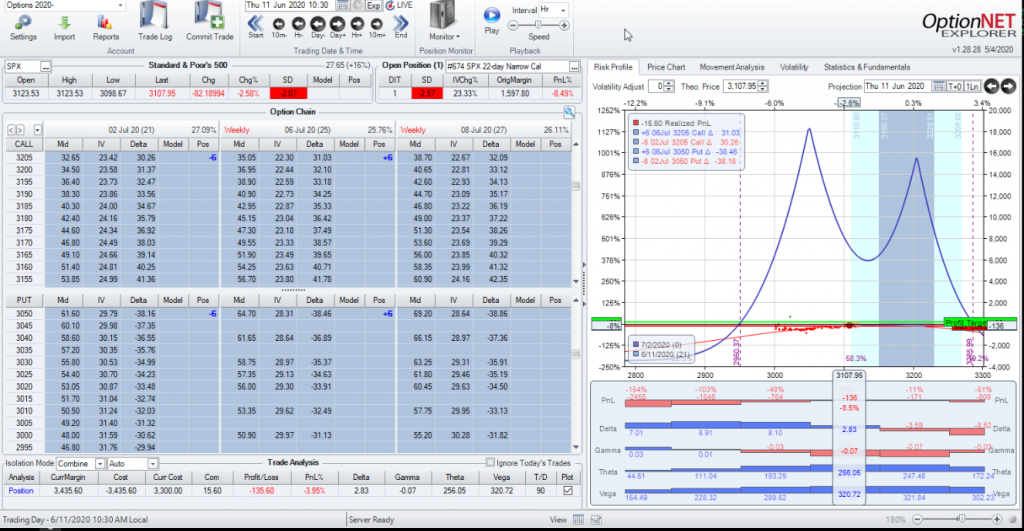

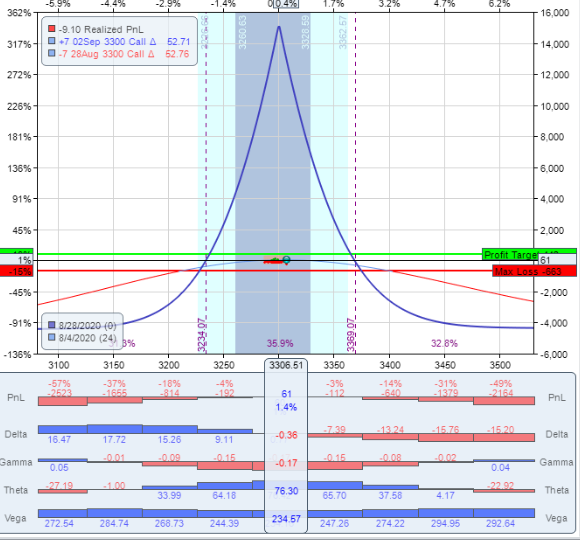

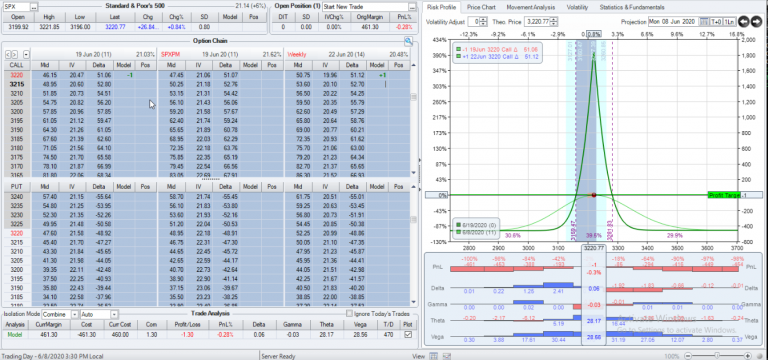

This is a very typical trade that I put on for much of this year. In the crazy market we’ve had this year, I really like the initial room this trade has and the relatively low vega exposure for a calendar. However, the very next morning I woke up to this: So in the first hour of trading SPX is down 2 SD and my trade is at an adjustment point. This was a rare exception where I was able to put on lower calendars as an adjustment. Had I not been able to get a good price on it, I would have gone right to the put, but since I was able to do so it looked like this:

So in the first hour of trading SPX is down 2 SD and my trade is at an adjustment point. This was a rare exception where I was able to put on lower calendars as an adjustment. Had I not been able to get a good price on it, I would have gone right to the put, but since I was able to do so it looked like this: So I got my double calendar on and I have a lot more room now, right? Not so fast, later that same day….

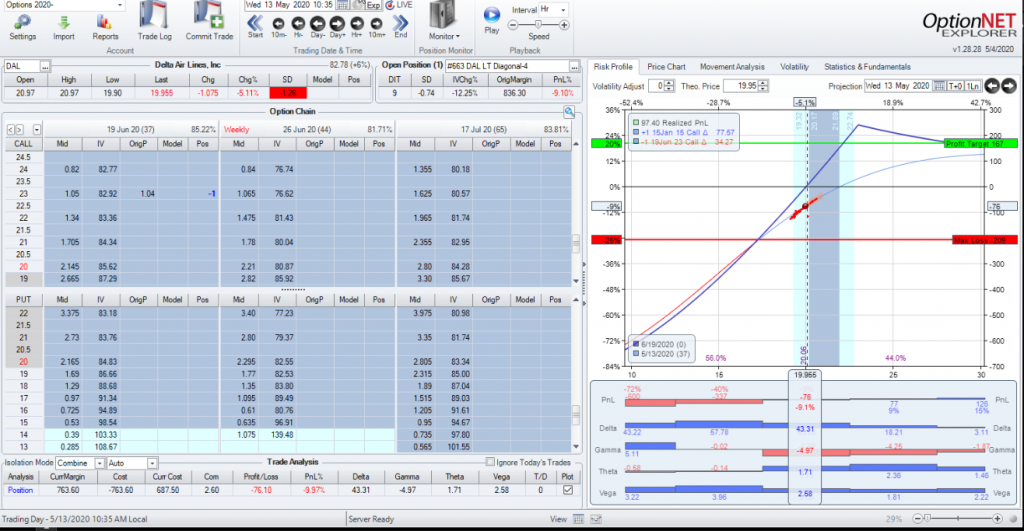

So I got my double calendar on and I have a lot more room now, right? Not so fast, later that same day…. Just 2 hours later, SPX is now 133 points down or 3.3 SD down. At this point there is no way I’m going to try and take off the upper calendars (I was lucky enough to get the lower calendars on when I did), so I go ahead an buy a put:

Just 2 hours later, SPX is now 133 points down or 3.3 SD down. At this point there is no way I’m going to try and take off the upper calendars (I was lucky enough to get the lower calendars on when I did), so I go ahead an buy a put: By buying a 2400 put in the back side of the calendar I was able to cut my position deltas to 1.8 from 5.4 and stop any more bleeding. The next day, the market calmed down and I was able to properly take off the upper calendars. At that point I was able to sell off the put since, with my proper adjustment, it was no longer needed.

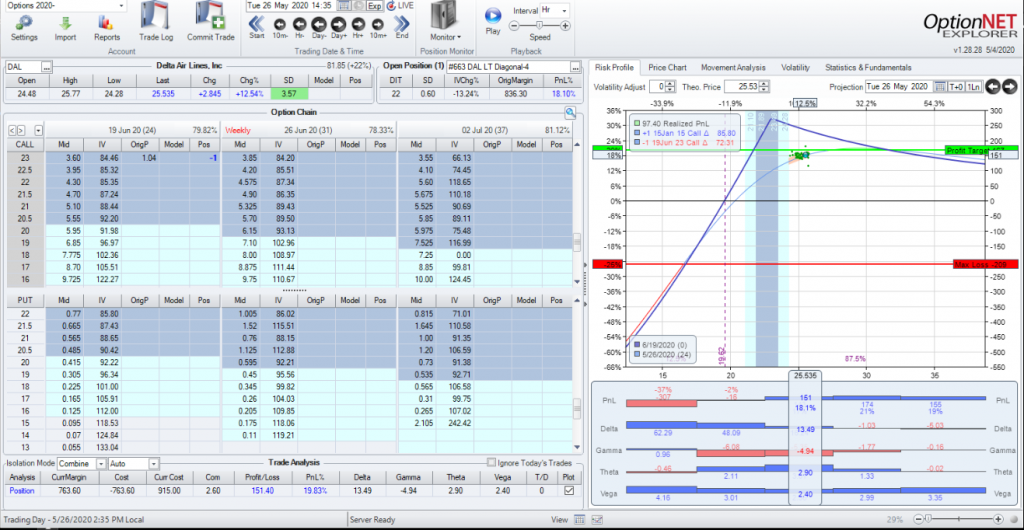

By buying a 2400 put in the back side of the calendar I was able to cut my position deltas to 1.8 from 5.4 and stop any more bleeding. The next day, the market calmed down and I was able to properly take off the upper calendars. At that point I was able to sell off the put since, with my proper adjustment, it was no longer needed. Now the trade is back to normal and, in this case, I was able to sell the put off at a profit. While that was never the goal, it was a nice bonus. This trade ended up doing very well (over 30% profit) and it was made possible by being able to weather the quick storm that came through the market.

Now the trade is back to normal and, in this case, I was able to sell the put off at a profit. While that was never the goal, it was a nice bonus. This trade ended up doing very well (over 30% profit) and it was made possible by being able to weather the quick storm that came through the market.

If you have pets, as I do, you understand that they are more than just animal companions. To many of us, our pets are part of our family. We do our best to take care of them, feed them, get their shots, make sure they have the best life we can give them. When they get sick, we collectively spend billions of dollars a year getting them the best medical care we can. When they die, we mourn them. And, outside of truly obsessive behavior, all of that is perfectly fine and normal. We take in these animals, keep them in our homes and our lives and treat them and protect them as our own.

If you have pets, as I do, you understand that they are more than just animal companions. To many of us, our pets are part of our family. We do our best to take care of them, feed them, get their shots, make sure they have the best life we can give them. When they get sick, we collectively spend billions of dollars a year getting them the best medical care we can. When they die, we mourn them. And, outside of truly obsessive behavior, all of that is perfectly fine and normal. We take in these animals, keep them in our homes and our lives and treat them and protect them as our own. A farmer or rancher also has animals. He takes them in, feeds them, and protects them. But it’s very different. Those animals are not part of his family. His goal is to eventually sell these animals to make his living. If one of his animals gets sick, he is far less patient with medical care. Time and costs matter and he can’t let one sick cow infect the entire herd. While he may try some limited things to make that cow better, if that fails the cow must be put down and he moves on and focuses on the rest of the herd. To the rancher, the animals are a business asset. They exist to make him money to feed and protect his family (and his family’s pets). But he doesn’t have the emotional attachment to his cattle like he has with his pets.

A farmer or rancher also has animals. He takes them in, feeds them, and protects them. But it’s very different. Those animals are not part of his family. His goal is to eventually sell these animals to make his living. If one of his animals gets sick, he is far less patient with medical care. Time and costs matter and he can’t let one sick cow infect the entire herd. While he may try some limited things to make that cow better, if that fails the cow must be put down and he moves on and focuses on the rest of the herd. To the rancher, the animals are a business asset. They exist to make him money to feed and protect his family (and his family’s pets). But he doesn’t have the emotional attachment to his cattle like he has with his pets.