Surviving Wild Market Drops

Originally posted on November 2, 2020

If you’ve followed my style of trading you know I like non-directional income style trades where I try to make money on time decay (positive theta). Most of the time, this works out well. I do lose on occasion as everyone does but I go into each trade with a plan to handle various market conditions. Most of my trades have enough time that I can adjust them if the market moves too far against my position. This, essentially, allows me to buy more time to allow the trade to work. If you’ve watched my This Week @MidwayTrades series, you’ve seen me execute this plan over and over again. Most of the time on these income trades my adjustment plan involves adding structures such as butterflies or calendars making a double or removing a structure from a double and returning to a single.

But there is one kind of move where this does not always work: A big market drop. I work hard to keep my trades in a good enough position to handle at least a 1 standard deviation move in either direction. Statistically, a stock should move less than that about 67% of the time so this keeps my trade in a relative safe position. On the bigger moves, I can make adjustments as described above. But what about a 2 SD move? Or even more? These moves tend to be on the downside so that’s where I’m going to focus this post. We do get occasional big crash moves and just adding or removing spreads isn’t going to work well because pricing is all over the place. Finding a steady price for 2 or 3 legs in a spread just is not practical, and legging out one at a time can be just as dangerous. You may be able to get out for some price, but that price could be really bad and make a big loss. As traders, we like to avoid big losses so what can we do to try and ride out the crazy storm?

Back To Basics

As one learns more about trading and gets more sophisticated with multi-legged trades, it’s easy to forget why options were created in the first place. In short, they act as insurance to protect a position. Traditionally that position was a long or short position in a stock, but it works just as well to protect a position made entirely of options. And for a big drop, that answer is simple: long puts. A properly purchased single long put can save your position and, in some cases, your account (if it got that bad, I would strongly suggest you are trading too large, but it still works). The simple act of adding a long put to a position at the right time can make the difference between a big loss and a small loss, or even a win. They come with a consequences, of course, so I do not like to use them all the time but, at the right time, a long put is a simple fix to a bad problem.

So this post will look at when I buy them, what I buy, and when I sell them. You may tweak these to suit your style, of course, but don’t think a trading plan is complete without having this as a possible response to a big down move.

When to Buy Puts

Buying puts is not a free pass. First, they cost money. You are sinking money into a trade that has gone badly. If done at the wrong time, you can easily dig a bigger hole for your position and take a bigger loss than needed. In addition to costing money, long puts reduce theta. All long options have negative theta so adding a long put to a position will hurt the theta of the position (maybe even taking it from positive to negative). As one who likes positive theta trades, this isn’t my goal. But when things get really bad, sometimes theta has to take a step back to the threats of delta and gamma (i.e. price movement risk). When delta and gamma get out of control quickly, a long put can stop the bleeding and give you time to catch your breath when things are going wild. This has an added benefit of allowing you to think clearer about your next move. If done properly, the stock can continue to tank and you’ll be just fine. Very few good things come from a state of panic so fixing the big problem in front of you helps with the next decision.

With all that being said, my guidelines for buying a put are the following conditions:

The stock has moved at least 1.6 standard deviations down. Less than that and my regular adjustments should work just fine. This is a guideline so don’t take it too literally but I think it’s a good rule of thumb. It’s beyond this point where prices tend to get weird and buying or selling a spread gets really difficult. But in a big down move, buying a put is easy as there are plenty of folks willing to sell them.

My position is at an adjustment point. There’s no sense buying long puts if the trade is still working even with the big move down. Sometimes, my trade can withstand a 2 SD move down. If that’s the case, there’s no need to add long puts.

What To Buy

So that’s when I buy puts, but now what puts do I buy? The critical idea here is to not buy too much or too little. As I stated before, options aren’t free in terms of cost or in terms of the Greeks so my goal is to buy just enough but not much more.

My guideline here is based on the delta of the position at the time I am buying the put. I want to buy enough to nearly flatten my position deltas such that further big movements won’t harm me. This means I’m looking to cut them around 80%. Yes, that’s a big delta cut but this is in response to a big move. That being said, this usually means I am buying far out of the money. This has the advantage of being less expensive while still getting the job done. If, for some reason, I need a lot of deltas, there’s nothing wrong with still buying far out of the money but buying multiples to get to the target. Which to do would be based on the price of the options you are considering. For example if I needed 40 deltas. I could but a .40 delta put or I could consider buying 2 .20 delta puts. Both will do the job so I would choose which ever is cheaper. Most of the time I don’t need anywhere near that many deltas so a single put will suffice.

But there is still the question of expiration. This depends on the spread I am trying to protect. If it is a vertical style spread where all the options are in the same expiration (this includes butterflies, condors, etc.), then I tend to buy in the same expiration as the spread. The only exception to that would be if there were very little time left in which case I would go further out in time. I’ll explain how far when I talk about when to sell, but as I tend to not be in trades during expiration week, this rarely comes into play. If the trade involves spreads in different expirations (e.g. calendars or diagonals), then I will use the later expiration.

When To Close the Put

The final piece of my hedge plan is when to close it. The temptation here is to look at the price paid for the put and base when to close it on the profit or loss of that put, essentially looking at it as a trade within a trade. I don’t do that. This long put hedge is part of my trade and so I try to look at it in terms of the what it’s doing for my trade. The goal isn’t to make money on the put (although that can happen), but to make money on the entire trade which now has this put as a part of it. So there are 4 times I look to close the long put hedge.

When I’m ready to simply close the entire trade. If I have hit my profit target or my max loss on the entire trade and it’s time to close the trade, then it’s time to close the put along with it. Again, the put is not separate from the trade.

When the market calms down and I can do a proper adjustment. So let’s say we had a big drop and I added a put, but the next day things are calm and a normal adjustment to the trade is now possible. The storm is over, I can buy that new spread or close the upper part of the double. Once I do that, my Greeks will be out of whack due to the long put. If I can do the regular adjustment, I will close the put after I get the adjustment done. Do not do it before because until that adjustment is on, the trade is still at risk.

The trade recovers. Sometimes a big drop if followed by a recovery. Maybe it’s the next day, maybe two, maybe even the same day in a really crazy market. If the market recovers such that my trade doesn’t need the help anymore, I will close the put for a loss. That leads to the question “what is a sufficient recovery?”. For me, a sufficient recovery is if the underlying comes back far enough to cross the center to the structure (or, in the case of a double, the center of the lower structure). There’s a big temptation here to take it off earlier to take a smaller loss on the put. The danger here is that if the stock drops back down again, you bought high, sold low, and potentially bought high again. That’s not a formula for profit. So the key here is to be patient and keep the insurance until the chances of needed it are lower.

Time. Long options have time decay. As they decay, the help they provide your trade diminishes. My rule of thumb is I will keep a long put on for up to 20% of the time remaining when I bought it. So if when I bought the put it had 20 days to expiration, I will keep it for up to 4 days. This would be the exception to the rule above on what expiration to buy. If there isn’t much time left in the spread, then buying the put in that expiration may not make sense based on the 20% guideline. In that case, I would consider buying something further out to avoid having to close it too quickly. If time runs out on the put and I still need the protection, I simply roll it out to a later time with the needed delta help.

Real World Examples

I’ve thrown a lot of information in this post so I think it’s valuable to show some examples of trades I’ve done where I’ve deployed this strategy. This year has certain had some volatility, so it wasn’t too difficult to find examples that demonstrate my methodology.

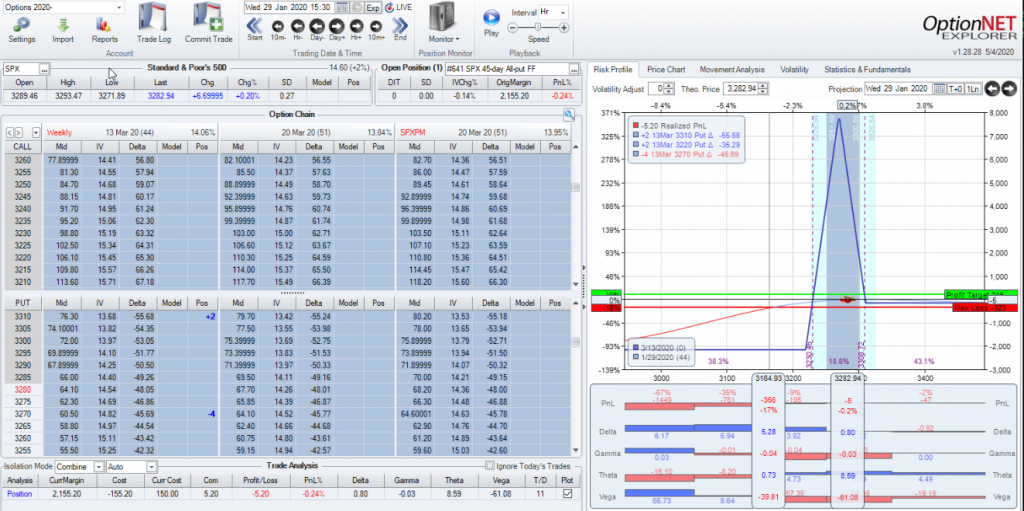

Back on January 29 I put on a simple butterfly:

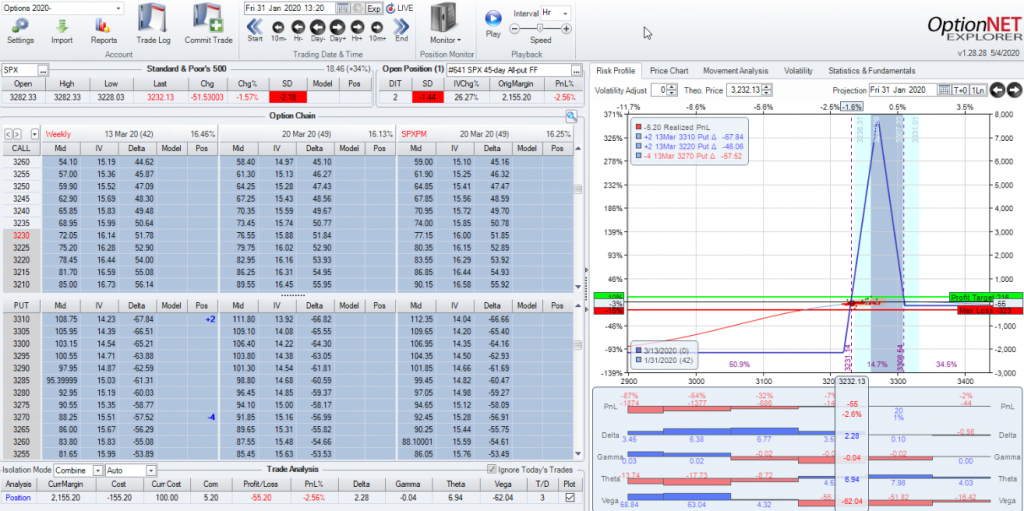

This is a common setup for a butterfly for me. It’s an unbalanced butterfly 44 days out, 40 points up, 50 points down which makes a nice flat delta trade with .80 deltas on a 2-lot. However, 2 days later the trade looked like this:

This is a common setup for a butterfly for me. It’s an unbalanced butterfly 44 days out, 40 points up, 50 points down which makes a nice flat delta trade with .80 deltas on a 2-lot. However, 2 days later the trade looked like this:

SPX moved 51 points down in a day which constituted a 2 SD move. My trade is at an adjustment point so instead of trying to buy a lower fly, I add a put:

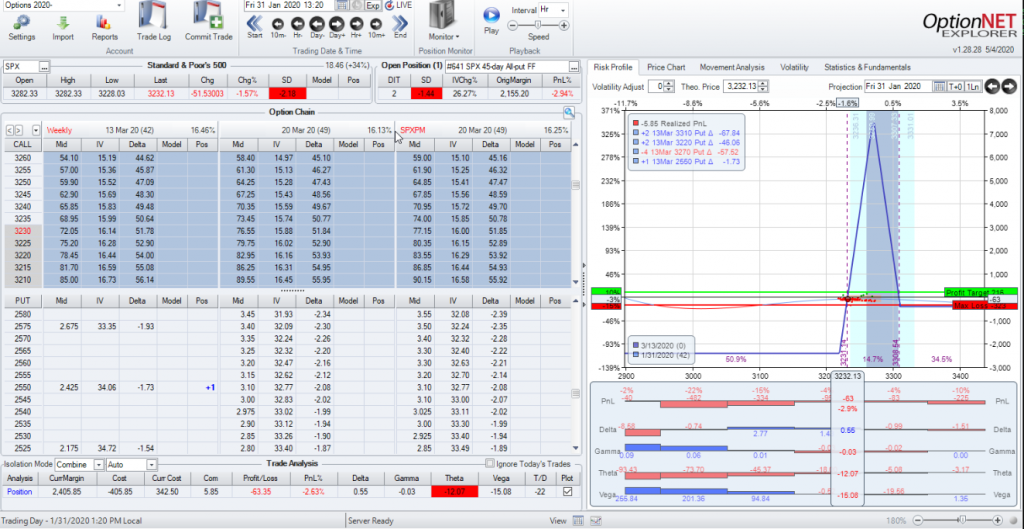

SPX moved 51 points down in a day which constituted a 2 SD move. My trade is at an adjustment point so instead of trying to buy a lower fly, I add a put:

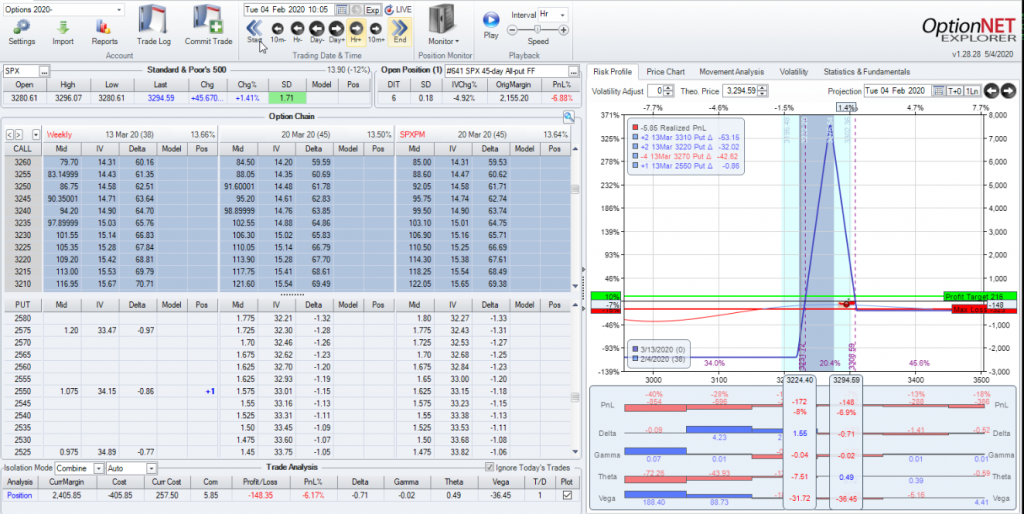

I bought a 2550 put (way out of the money). This is because to cut my deltas by about 80% I needed around 1.75 deltas. But now I’m not worried about the trade getting into trouble on the downside and I can wait it out and see what happens given that I’m really flat so that price movement doesn’t scare me. In return for that, my position is negative theta at the moment. While I don’t like that, I’ll take it for now to help stop the delta/gamma bleeding. When I bought the put it had 42 days left in it. That means I’m willing to keep it on for about 8 days before I need to sell it outright or roll it out. This happens to be a Friday so I kept this put on over the weekend and even into the early part of the week. It wasn’t until Tuesday Feb 4 that the trade looked like this:

I bought a 2550 put (way out of the money). This is because to cut my deltas by about 80% I needed around 1.75 deltas. But now I’m not worried about the trade getting into trouble on the downside and I can wait it out and see what happens given that I’m really flat so that price movement doesn’t scare me. In return for that, my position is negative theta at the moment. While I don’t like that, I’ll take it for now to help stop the delta/gamma bleeding. When I bought the put it had 42 days left in it. That means I’m willing to keep it on for about 8 days before I need to sell it outright or roll it out. This happens to be a Friday so I kept this put on over the weekend and even into the early part of the week. It wasn’t until Tuesday Feb 4 that the trade looked like this:

Note that we had a big up day that put the stock above the middle of the fly structure. At this point it’s time to sell it off at a loss. I lost a bit over 50% of the value of the put but it was just insurance that wasn’t needed. On the plus side, I didn’t pay much for it and this trade eventually closed for a small win. In perfect hindsight, I could have done nothing and done better but there was no way to know that at the time and it was better from a risk management perspective to buy the put and protect the position so that it did not get out of control and become a big loss.

Note that we had a big up day that put the stock above the middle of the fly structure. At this point it’s time to sell it off at a loss. I lost a bit over 50% of the value of the put but it was just insurance that wasn’t needed. On the plus side, I didn’t pay much for it and this trade eventually closed for a small win. In perfect hindsight, I could have done nothing and done better but there was no way to know that at the time and it was better from a risk management perspective to buy the put and protect the position so that it did not get out of control and become a big loss.

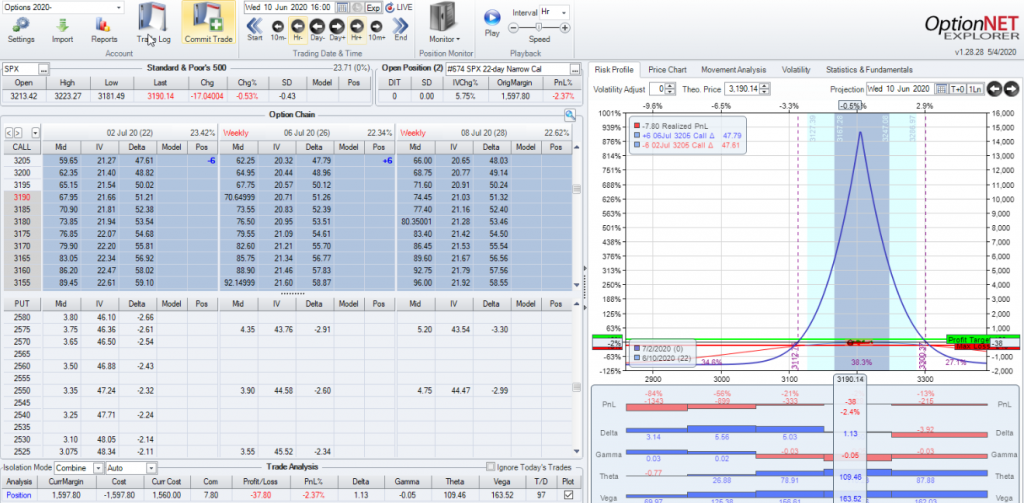

Another interesting example was on June 10 when I put on a narrow calendar.

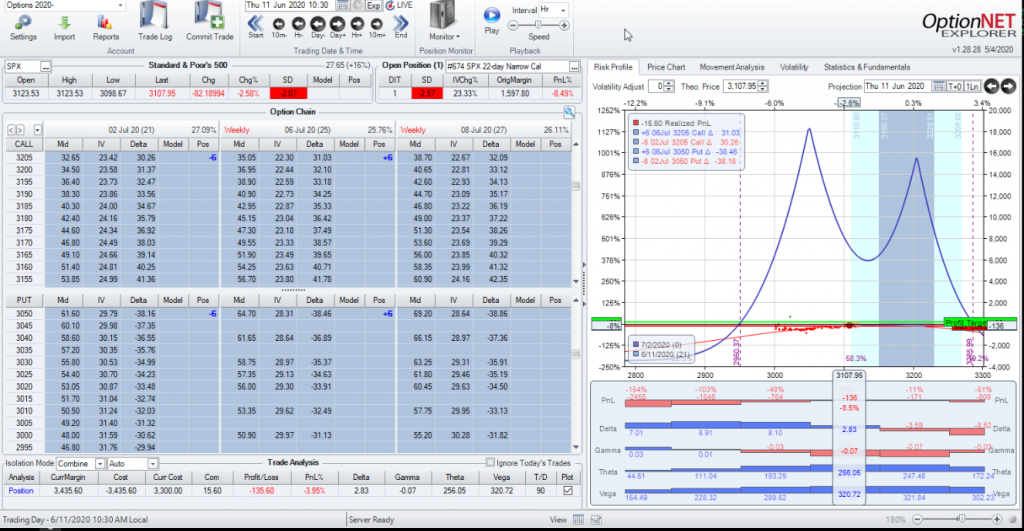

This is a very typical trade that I put on for much of this year. In the crazy market we’ve had this year, I really like the initial room this trade has and the relatively low vega exposure for a calendar. However, the very next morning I woke up to this:

This is a very typical trade that I put on for much of this year. In the crazy market we’ve had this year, I really like the initial room this trade has and the relatively low vega exposure for a calendar. However, the very next morning I woke up to this:

So in the first hour of trading SPX is down 2 SD and my trade is at an adjustment point. This was a rare exception where I was able to put on lower calendars as an adjustment. Had I not been able to get a good price on it, I would have gone right to the put, but since I was able to do so it looked like this:

So in the first hour of trading SPX is down 2 SD and my trade is at an adjustment point. This was a rare exception where I was able to put on lower calendars as an adjustment. Had I not been able to get a good price on it, I would have gone right to the put, but since I was able to do so it looked like this:

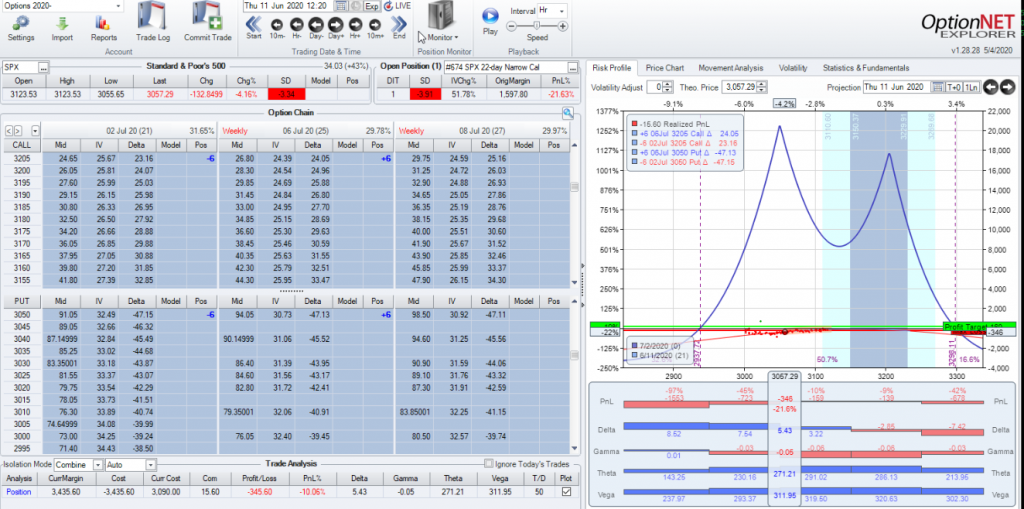

So I got my double calendar on and I have a lot more room now, right? Not so fast, later that same day….

So I got my double calendar on and I have a lot more room now, right? Not so fast, later that same day….

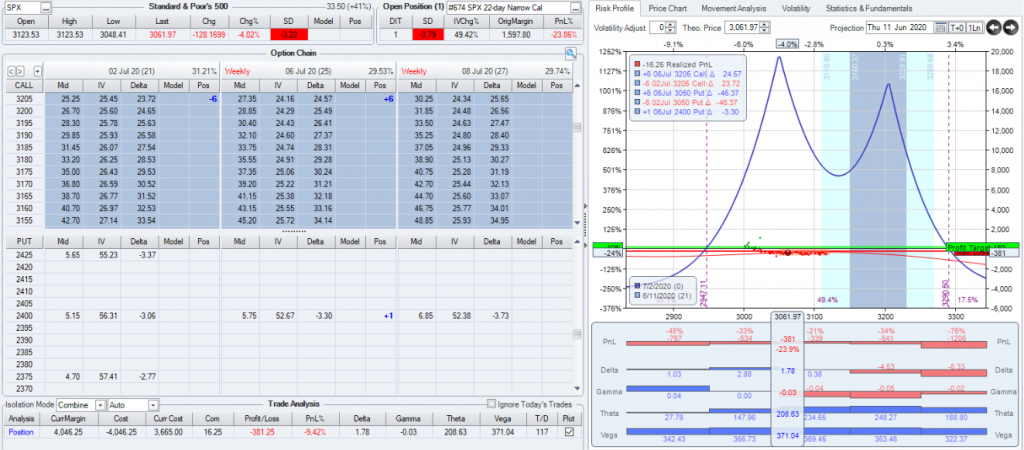

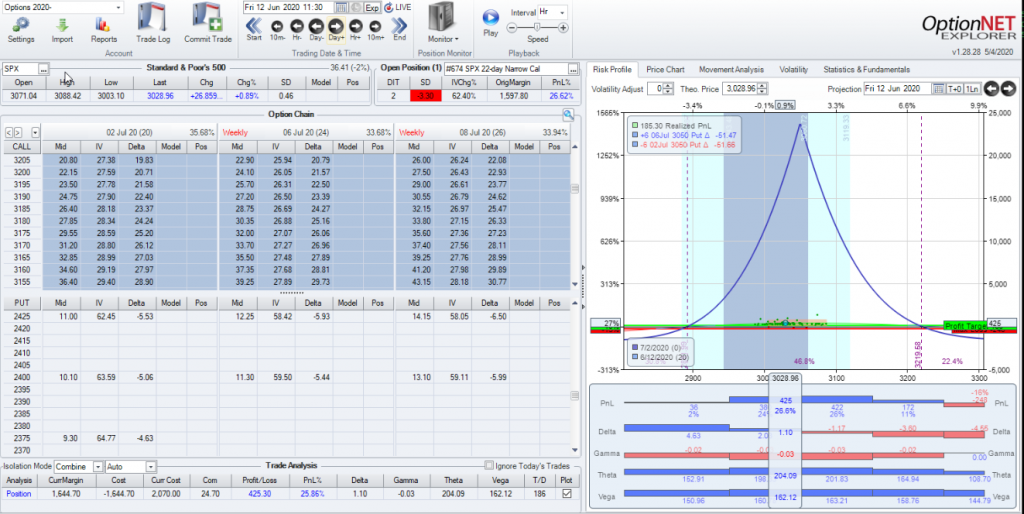

Just 2 hours later, SPX is now 133 points down or 3.3 SD down. At this point there is no way I’m going to try and take off the upper calendars (I was lucky enough to get the lower calendars on when I did), so I go ahead an buy a put:

Just 2 hours later, SPX is now 133 points down or 3.3 SD down. At this point there is no way I’m going to try and take off the upper calendars (I was lucky enough to get the lower calendars on when I did), so I go ahead an buy a put:

By buying a 2400 put in the back side of the calendar I was able to cut my position deltas to 1.8 from 5.4 and stop any more bleeding. The next day, the market calmed down and I was able to properly take off the upper calendars. At that point I was able to sell off the put since, with my proper adjustment, it was no longer needed.

By buying a 2400 put in the back side of the calendar I was able to cut my position deltas to 1.8 from 5.4 and stop any more bleeding. The next day, the market calmed down and I was able to properly take off the upper calendars. At that point I was able to sell off the put since, with my proper adjustment, it was no longer needed.

Now the trade is back to normal and, in this case, I was able to sell the put off at a profit. While that was never the goal, it was a nice bonus. This trade ended up doing very well (over 30% profit) and it was made possible by being able to weather the quick storm that came through the market.

Now the trade is back to normal and, in this case, I was able to sell the put off at a profit. While that was never the goal, it was a nice bonus. This trade ended up doing very well (over 30% profit) and it was made possible by being able to weather the quick storm that came through the market.

In these examples I used long puts to save trades that got hit by a big market drop. Long puts are not a cure for every trade. I have used these and still lost money, although not as much as I would had I not bought the put. But long puts can be the right fix for a crazy down move.

Hopefully you found this helpful. I’d love to hear what you think or other ideas you may have to handle these kinds of big moves. Feel free to comment here or reach out me directly at midway@midwaytrades.com

This content is free to use and copy with attribution under a creative commons license.